The twenty-year-old woman who challenged Hindu patriarchy; and won

From child bride to doctor - Rukhmabai's journey

Hi there,

While working on my series about how modern-day India came together, read it here, I went down a fascinating rabbit hole of learning about one of India’s first female doctors.

Rukhmabai was a radical: an intellectual, full of ambition and courage to chase after her dreams.

Born at a time when girls were trained to have babies and take care of the house, she defied Hindu norms.

In an era when child marriage was customary, she was married off at eleven. However, she refused to live with her husband and walked away from a marriage she did not consent to. With the help of fellow reformers, she went to England to become a doctor.

In 1895, she started working as a doctor in Surat, where she was awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Silver Medal for her service during the plague epidemic. She worked for over thirty years, primarily in the field of women's health—a neglected area, inspiring generations of women after her.

Let’s dig in.

Rukhmabai's Early Life

Rukhmabai was born in 1864 or 1865. She was the only child of Jayantibai and Janardan Pandurang. Her father died when she was two and a half years old. Fortunately, Jayantibai's father, Harishchandra Yadavaji, brought his seventeen-year-old widowed daughter and little granddaughter to stay with him.

Harishchandra had the means and will to look after his family. Working as an official in the Public Works Department, he owned a house near the French Bridge in Gamdevi, Bombay. He would later be honored by the government with the title of Rai Bahadur.

Before his death, Janardan had hastily made a will transferring his assets – property worth around Rs.25,000 – to his wife. This fortune, which included a house inherited from his father and additional property bought from his earnings as a contractor, was considerable for those days. The will was crucial to ensure Jayantibai would be taken care of, as it wasn’t unheard of for relatives of the deceased to take over the property, leaving widows to bear hardships with no assets to their name.

In Jayantibai’s community, Suthars - carpenters, a lower caste community, widow remarriage was permitted. This was unusual for the time, as widows generally had no standing in society. They were considered inauspicious, and a woman without a man was seen as an oddity. Harishchandra started looking for an eligible suitor. The search lasted six years, but the wait proved worthwhile when he found a suitable match.

The thirty-four-year-old Dr. Sakharam Arjun was a distinguished physician working at Grant Medical College and a founding member of the Bombay Natural History Society. He could have his pick.

Fearing rejection, Jayantibai, a widow with an eight-and-a-half-year-old daughter, did the unthinkable: she sent Sakharam a letter expressing her wish to be his life partner. The chivalrous doctor, impressed by her daring, accepted her proposal.

In doing so, Sakharam chose to go against societal norms, marrying a widow with a child.

Sakharam was a self-made man, born into a poor Marathi family, widowed at thirty. Through merit and hard work, he built his reputation as a social reformer - a leading voice in public education on health and women's education. He was also referred to as "Lord" and was perceived as being rich with his house being described as palatial.

The stars seemed to have aligned for Rukhmabai and her mother.

Child Bride at Eleven

But then, eleven-year-old Rukhmabai was married to nineteen-year-old Dadaji Bhikaji.

There was nothing special about Dadaji. He was a sickly school dropout from an undistinguished family.

So why did Sakharam, a liberal man, choose him and marry off Rukhmabai so early?

Sakharam is believed to have acted in self-interest.

Before his marriage to Jayantibai, the substantial property from her first husband, Janardan Pandurang, was transferred to Rukhmabai.

This move was designed to preempt any claims Janardan's kin might make following Jayantibai's remarriage.

The courts, while interpreting the Hindu Widows Remarriage Act, had passed conflicting decisions on whether a woman could own her deceased husband's property after remarriage.

Once Rukhmabai married, the property would go to her husband's family. Dadaji, was distantly related to Sakharam. He seemed unlikely to stand up to an affluent and powerful father-in-law. As a further safeguard, Sakharam arranged with Dadaji's mother that her son would be a ghar jamaai, staying with his in-laws.

Under Sakharam's thumb, Dadaji was forced to return to school and become an educated man. Under this arrangement the property would be under Sakharam’s control.

But this plan backfired.

Dadaji's mother died four months after the marriage, and he abandoned his transformation. He stopped attending school and went back to being an idler, having no steady income or job prospects and lived as a loafer under his maternal uncle Narayan Dhurmaji's care.

Rukhmabai's life meanwhile took a drastic turn. With her mother-in-law in charge of her activities, she was forced to drop out of school. The irony of Dadaji going to school to become a good husband while she was compelled to stop was not lost on her.

At Sakharam's house, she had cultivated liberal ideas having access to the leading social reformers and scholars of the time who frequented Sakharam’s home. Sakharam encouraged young Rukhmabai to cultivate contacts with European ladies like Dr. Edith Pechey, who broadened her horizons and became pillars of support. She frequented Bombay's Christian mission houses and libraries. She attended the special lectures organised by the Prarthana Samaj1 and Arya Mahila Samaj. She removed time from her responsibilities of taking care of her half-siblings to read and educate herself.

A product of diverse worldviews under Sakharam's tutelage, her early marriage steamrolled over her beliefs.

Six months after marriage, Rukhmabai reached puberty. Custom required garbhadhan – consummation with the intent to have a child. But Sakharam objected, saying early consummation would result in a weak child.

Early marriage and having children early were the norm at the time. The average life span was below 30 years, and having many children was expected.

Life was governed by Hindu shastras, texts that went unquestioned. Colonial law avoided interfering with Hindu laws unless absolutely necessary, and Hindu law gave men power over women's lives. Education was women's only weapon against this power dynamic.

Sakharam seemed to realize his mistake as Dadaji neglected his duties, left school, and fell into bad company. When Dadaji fell ill with consumption, Sakharam nursed him back to health.

However, under various pretexts, Sakharam delayed sending Rukhmabai to her husband, citing Dadaji's lack of a proper home, means to provide for her, and poor health.

As time passed, it became apparent that Sakharam wouldn't let go of Rukhmabai. Frustrated, Dadaji, supported by his uncle Narayan, filed a case claiming restitution of conjugal rights.

The case for her independence

Tensions were running high. Neither Rukhmabai's mother, Jayantibai, nor her grandfather, Harishchandra, understood Rukhmabai's horror at the prospect of living with Dadaji. They wanted to make the marriage work. While they harbored no illusions about Dadaji, they were unwilling to let their family honor be reduced to tatters by Rukhmabai's refusal to respect the sacred bond of marriage.

Rukhmabai was warned about the consequences: she could not marry someone else while Dadaji lived, and divorce was not permitted by either custom or law.

She was cautioned that her defiance might harm the very women for whose rights she was fighting. If she questioned her marriage on the grounds that she was too young to give consent when wed, it could encourage men to leave their wives at will, arguing that these unfit wives had been forced upon them when they were incapable of consenting. However, in this skewed power dynamic, men already had the ability to leave their wives and marry another. Multiple wives in Hindu families were common.

Five months before the case was heard, Sakharam died. He had backed Rukhmabai's decision, lending her support. She had lost her protector. Deeply grateful for the stability Sakharam had provided, she never felt like a "step" child and had been well cared for.

She was supported by her mother and grandfather after Sakharam's death when they realized she was all alone. Additionally, people from different spheres of public life came together to organize funds and gather support for her, including the fiery poet and writer Behramji Malabari2.

Within months of the filing of Dadaji Bhikaji vs Rukhmabai, Malabari published ‘Notes on Infant Marriage and Enforced Widowhood’, a pamphlet sent to 4,000 leading Englishmen and Hindus. In it, Malabari deplored the evil of "baby marriage" and demanded laws to prevent it. Similarly, on the issue of remarriage for widows, Malabari criticized the practice of prohibiting it. He argued that it was due to inaccurate interpretation of scripture by priests, which caused a girl after ten to be treated as a serpent in her parents' house. His "Notes" led to heated debates in the public domain and culminated in the Age of Consent Act. The Act raised the age of consent for sexual intercourse for all girls from ten to twelve years. While not directly related to Rukhmabai's case, Malabari's work highlighted the broader issues of women's rights that her struggle exemplified.

Another supporter was Henry Curwen, who as the editor of the Times of India, wielded considerable influence. He ensured elaborate pro-Rukhmabai coverage of the case. He also convinced Rukhmabai to write about her experience under the pseudonym ‘A Hindu Lady’ - the letters were published and drew attention to the plight of girls in India.

In September 1885, Rukhmabai's case came up for hearing before Justice Pinhey in the Bombay High Court. It was the first of its kind—challenging Hindu marriage.

Dadaji's case rested on the belief that Hindu marriage was sacrosanct. For his lawyers, it was open and shut. The burden was on Rukhmabai to prove she was justified in resisting her husband's suit to enforce his marital rights.

She couldn't argue that she was too young to give intelligent consent. According to an authoritative interpretation of Hindu Law, the spouse's consent wasn't required to establish the validity of a marriage.

A Hindu marriage became binding the moment the prescribed sacrament was performed; it was a religious duty. Consummation or cohabitation in the husband's house were not essential for the marriage to be valid.

Before the 1857 transition from East India Company rule to British Crown rule, suits for restitution of conjugal rights had no foundation in Hindu law. However, with the restructuring of the court system post-1857, English legal practice became part of the British India legal regime.

In England, a formidable body of case law had been developed for restitution of conjugal rights, and Justice Pinhey was bound by this case law.

Rukhmabai's team of lawyers needed to creatively interpret the intricacies and principles of both English and Hindu laws to win her case.

Justice Pinhey found it cruel to force Rukhmabai against her wishes to live with her husband. He had an epiphany on how to rule in Rukhmabai's favor without even needing to hear from her defense lawyers.

According to Justice Pinhey,

“It is a misnomer to call this a suit for the restitution of conjugal rights. For: The parties to the present suit went through the religious ceremony of marriage eleven years ago when the defendant was a child of eleven years of age. They have never cohabited. And now that the defendant is a woman of twenty-two, the plaintiff asks the Court to compel her to go to his house, that he may complete his contract with her by consummating the marriage.”

No court had ever ordered a married woman to go to her husband and allowed 'that man to consummate the marriage against her will'. Never had commencement of cohabitation, as distinguished from its resumption, been judicially ordered.

Conjugal rights had not been instituted in the case brought before him. Dadaji had prayed 'in the alternative, for a restitution or institution of conjugal rights'. This plea left Justice Pinhey with the discretion to grant "institution," and Pinhey was free to decide whether to accept or refuse the request. Pinhey refused, thus rejecting Dadaji's claim.

Overnight, Rukhmabai became a celebrity. Following Pinhey's verdict, she was hailed as a champion of "the rights of Indian womanhood." At just twenty-two, she had battled Hindu dogma and emerged victorious. News of her win spread far and wide in England.

However, Rukhmabai's fight was far from over, and she would need all the support she could get.

Rukhmabai faced fierce opposition from conservative elements of Hindu society. Her win threatened the foundation of the family institution, suggesting that Hindu wives could refuse to go to their husband's home because they disliked them.

The Hindu Orthodoxy led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, denounced her as a self-centered, willful woman whose head had been swollen by English education. Aided by a misguided English judge; she had caused a "revolution" that was "entirely subversive of the principles that have governed Hindu society for ages." Through his weeklies, the English Mahratta and the Marathi Kesari, Tilak portrayed Rukhmabai as the antithesis of what a good Hindu woman should be.

Tilak believed that education would hinder women from performing their chief duty: being wives and mothers. If an education was to be delivered, it should focus on religious instruction and household skills, he argued. Writing in The Mahratta, he claimed women were "incapable of understanding English, history, mathematics and science as it interfered in the natural aspect of a woman's life. So the girls should be taught at the most Sanskrit, sanitation and needlework. Teaching Hindu women to read English would ruin their precious traditional values and would make them immoral and insubordinate."3

An educated woman from any caste, and especially from a lower caste, was terrifying to the orthodoxy.

Dadaji's case was now taken over by Hindu traditionalists, and an appeal was filed.

The appeal was heard by Chief Justice Sargent and Justice Bayley in March 1886. The ordeal for Rukhmabai began anew.

The battle continues

This time, Dadaji's chief counsel, Macpherson, raised two points in rebuttal to Pinhey's ruling:

He argued that this was a case of the institution, not restitution, of conjugal rights.

Macpherson insisted that the Court had no discretion in this matter as the case fell under Hindu customs.

Rukhmabai's lawyers countered:

The law relating to institution or restitution of conjugal rights was alien to Hindu law.

The present case was unprecedented—no English authority had ever enforced the commencement of cohabitation. They questioned how the court would enforce a restitution decree.

Macpherson however was able to convince the judges in two ways:

He used English case law to bolster his argument. To address the claim that the case was foreign to Hindu law, he employed clever negative logic, arguing that Hindu law "contains nothing forbiding" a suit for restitution, which includes the institution of conjugal rights. Thus, he contended, Dadaji was entitled to the company of his wife.

He urged the judges to decide as per Hindu law.

The two judges overturned Pinhey's judgment, ordering the case to be retried.

As the debate across the country regarding child marriage grew more polarized and divisive, Rukhmabai wrote a letter to Queen Victoria in April 1887, published in The Times of India:

“At such an unusual occasion [Queen Victoria’s 50th year of rule] will the mother listen to an earnest appeal from her millions of Indian daughters and grant them a few simple words of change into the book on Hindu law- that 'marriages performed before the respective ages of 20 in boys and 15 in girls shall not be considered legal in the eyes of the law if brought before the Court.”

By this time, Rukhmabai believed that legislation was necessary for breaking the shackles binding women. She thought that colonial rule was beneficial in bringing about societal change. However, Queen Victoria did not intervene in her case.

The case resumed eleven months later, in March 1887, in the court of Justice Farran. Interpreting Hindu laws, Justice Farran ordered Rukhmabai to live with her husband or face six months of imprisonment and/or forfeiture of property. Rukhmabai was given one month to weigh her options.

Defiantly, Rukhmabai declared she would not live with Dadaji, preferring jail instead. An appeal was filed against Farran's judgment, delaying her potential imprisonment.

Rukhmabai turned a no-win situation into a victory.

If she went to jail, she would gain cult-like status for her beliefs. The Hindu orthodoxy knew they couldn't pursue the matter further—if it went to the Privy Council, they risked losing. Moreover, they had achieved their goal: the reversal of Pinhey's judgment. Hindu law remained unharmed.

A year later, the matter ended with a compromise. Dadaji received two thousand rupees from Rukhmabai 'in satisfaction of all costs'. He agreed not to assert any claims as a husband against Rukhmabai on her current or future estate, protecting her from all immediate and future complications.

Rukhmabai was now a free woman.

Although the compromise was difficult for Rukhmabai, rejecting it would have left her with two impractical alternatives: accepting the daily hell of cohabitation with Dadaji and abandoning the cause entirely, or courting punishment and becoming a sacrificial saint, knowing that the sacrifice would not further the women's cause beyond what she had already accomplished.

One of her lawyers, Telang, was also a social reformer. He believed in changing Hindu law from within, arguing that what custom has made, custom can also improve. By antagonizing the orthodoxy further, the reformers risked alienating the entire community. Telang felt it wouldn't bode well for a foreign power to intervene in Hindu domestic and socio-religious arrangements. He wanted the reformers to be sensitive to the Hindus' fears and to seek compromise.

After three years of hell, Rukhmabai was ready to move forward. The compromise, while not ideal, allowed her to regain her freedom and continue her fight for women's rights in a different capacity.

The pursuit of Medicine

Rukhmabai's choice to pursue medicine was guided by Doctor Edith Pechey, a member of the legendary Edinburgh Seven4, the first group of women to study medicine in Britain.

In 1882, American businessman George Kittredge and eminent social reformer Sorabjee Shapurjee Bengallee initiated what the Times of India described as the "medical women for India" movement.

They raised money to establish India's first hospital for women, the Cama Hospital in Mumbai, and set up the "Medical Women for India Fund" of Bombay.

One of the fund's objectives was to bring qualified British women doctors to India to set up and manage hospitals exclusively for women and children. Using this fund, Dr. Pechey was invited to take up the position of senior medical officer at the Cama Hospital.

Pechey, a pillar of support for Rukhmabai during her legal case, inspired her to pursue medicine in England. However, the costs of spending at least five years in the UK to complete her education would quickly add up.

Once again, Dr. Pechey came to Rukhmabai's rescue, reaching out to influential individuals and institutions in the UK to raise money for her education. She also enlisted the help of Eva and William McLaren, with whom Rukhmabai would stay for the first year to acclimate to London before moving to a hostel.

The McLarens were a prominent family, with Eva at the forefront of the suffragist movement. William McLaren's parents had supported the 'Edinburgh Seven' and were instrumental in ensuring that women were accepted as medical students at the University of Edinburgh.

Before her departure, Rukhmabai's two guardians—her mother and grandfather—were reluctant to see her go. They wanted her to promise three things: she would not eat beef, she would not marry an Englishman, and she would not renounce her religion to become a Christian. Rukhmabai readily gave the last two assurances but refused to abstain from beef, believing the revulsion to eating it was a superstition she did not share.

In 1889, at twenty-four, Rukhmabai left to study medicine in England.

Under the McLarens' care, she gained insight into the challenges faced by British women fighting for their own rights.

In 1890, Rukhmabai was accepted to the London School of Medicine for Women, co-founded by Sophia Jex-Blake, another member of the Edinburgh Seven. Hailed as the 'Mother school of all medical women in Great Britain and Ireland', it instilled professionalism and a missionary zeal for patient care in its students.

Studying in English posed a challenge for Rukhmabai. She would first formulate her thoughts in Marathi, mentally translate them into English, and then speak. This made her delivery slow and halting, causing her to feel awkward while speaking the language. However, the three female teachers—among a predominantly male faculty—closely followed each student's performance, addressing their particular problems and keeping them motivated.

In 1894, Rukhmabai earned the Triple Qualification. For her course, she completed nineteen subjects, six more than the thirteen prescribed for the examination. She also sought specialized training in various hospitals known for their excellence. After studying at the Leeds School of Medicine, she returned to London to gain further experience at the Royal Free Hospital. She then went to Dublin to acquire practical experience at the city's famous maternity hospital, the Rotunda.

A lifetime of practicing medicine

In January 1895, Rukhmabai returned to Bombay.

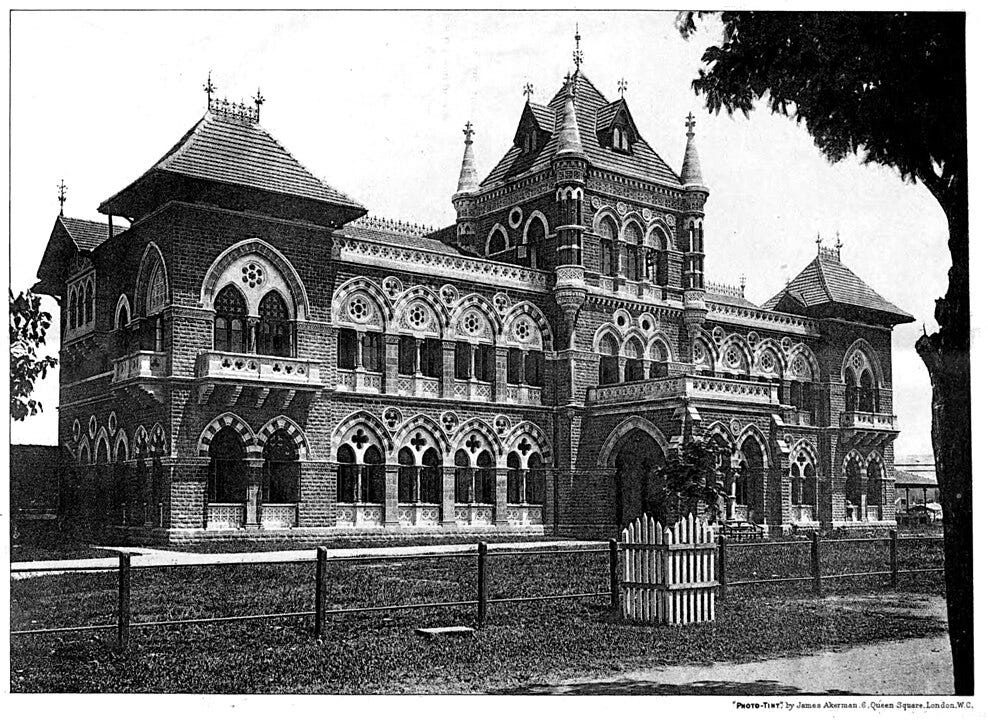

Shortly thereafter, she took charge of the newly established Seth Morarbhai Vrijbhukhandas Hospital and Dispensary for Women and Children in Surat, less than 200 miles from Bombay.

The hospital was set up partly from the funds raised under the Countess of Dufferin’s Fund. In 1885, three years after the medical women for India movement the British administration responded to the demand for female practitioners. The Countess of Dufferin’s Fund sought to create a network of hospitals and dispensaries for women and children and to provide education to women to become doctors.

The hospital was a two-storey stone structure situated in the bustling city center. The ground floor housed an outdoor dispensary, waiting room, consulting room, wards accommodating twenty indoor patients, and an office. Rukhmabai's modest apartment occupied the first floor, where she would reside for the next twenty-two years.

Shortly after the hospital's opening, a plague epidemic struck Surat. Rising to the challenge, Rukhmabai quickly learned Gujarati and went door-to-door tending to patients. For nine grueling months, she worked tirelessly without rest. Her dedication during the plague earned her the Kaisar-i-Hind Silver Medal.

Initially, women were hesitant to visit the hospital, preferring midwives or home remedies. They feared hospitalization, believing evil spirits might possess them there. This mistrust of Western medicine was compounded by the inability of male doctors to examine female patients.

To win over people’s trust, a myth goes, one day Rukhmabai spied a pregnant sheep that had strayed into the hospital and kept it back. The sheep gave birth inside the hospital and people saw that, unharmed by any evil spirits, both the mother and the newborn were healthy. Rukhmabai got the press to report the event and emphasize the safety of hospitalization.

Gradually, people began to overcome their reservations. The Parsi community was quick to embrace the hospital, while converting Hindus and Muslims proved a slower, more challenging process.

However, Rukhmabai's tenure in Surat was cut short due to difficulties in securing funds for expanding the number of beds at the hospital. At the age of fifty-two, after nurturing and developing the hospital as its first superintendent, as well as serving the Surati women and children for twenty-two years, she left for Rajkot.

In Rajkot, Rukhmabai took charge of the Rasukhanji Zenana Hospital, serving women from the surrounding 200-odd Kathiawad states. When an influenza epidemic struck Kathiawad, she once again rose to the occasion. Her efforts during this crisis were recognized with the addition of a bar to her Kaisar-i-Hind medal. However, as in Surat, chronic funding shortages hindered her plans and efforts.

Rukhmabai retired from medical practice at the age of sixty-five. For the next twenty-five years, she lived a quiet life in Bombay.

In 1904, following Dadaji's death, Rukhmabai made a surprising decision. She adopted the all-white sari – traditional widow's attire – and wore it until her passing more than fifty years later.

Reference Books

I hope you enjoyed reading Rukhmabai’s story as much as I did researching and writing it. I read her story in Sudhir Chandra’s book Rukhmabai: The Life and Times of a Child Bride turned Rebel-Doctor. If you enjoyed this article, you will love the book - the author portrays a vivid image of the challenges Rukhmabai had to face.

Kavitha Rao in her book Lady Doctors: The Untold Stories Of India's First Women In Medicine also covers Rukhmabai’s journey. But it fails to show the big picture. Also, her version differs from Sudhir Chandra’s when it comes to Sakharam wanting to control Rukhmabai’s property. But, she covers other pioneering “lady” doctors of India such as Anandibai, Kadambini Ganguly, Haimabati Sen, Muthulakshmi Reddy, and Mary Poonen Lukose. These are stories I wish I knew when I was younger.

Highly recommend picking up both these books❤️

P.S. I have this deep desire to talk to my two nieces, they are currently two-and-a-half-years-old, about the journey of these superwomen. When I was growing up, I don’t remember reading or knowing about strong Indian women leaders, I don’t want my nieces to grow up the way I did. So, if you have someone who finds strength in stories, please share Rukhmabai’s story with them.

In the next edition, we will return to the story of how India was united.

If you come across any stories that move and inspire you, do share them with me and I’ll let you know if they make an appearance in a future edition.

All the articles on Filtered Kapi take a lot of time, love and care to write. It really helps boost my confidence to keep going when readers interact by liking the post or better yet commenting and letting me know what they thought about it.

Filtered Kapi #65

Fun fact- The Prarthana Samaj was founded by Atmaram Pandurang. Pandurang was the other Indian founding member of the Bombay Natural History Society. Sakharam donated money for its ‘Prarthana Mandir’ and delivered some of its weekly lectures for women.

On a personal note, I grew up near the Prarthana Samaj area but can’t really pin down where the physical space of the Samaj is/was located. If you can find out let me know?

Fun fact- Behramji Malabari founded Seva Sadan Society in 1908 in Mumbai. The society is a place of refuge where impoverished and oppressed women of all communities can find protection, care, and a home.

From Lady Doctors: The Untold Stories Of India's First Women In Medicine by Kavitha Rao

Loved reading this very well-written article about an amazing woman. Thank you.

What a woman! So admirable. The story itself is not sufficient to inspire young minds. We also need storytellers who can instill the required inspiration in the listeners mind. All the very best to you for that crucial role.