How the British controlled a fractured India

A look at the relationship between the Crown and the Princely States via salt taxation, right to mint coins and administrative interference

Hi there,

1947 was a pivotal year for a newly independent India.

The leaders—namely Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Lord Mountbatten, and V.P. Menon—convinced, cajoled, and threatened the rulers of the princely states to give up their sovereignty and unite with India.

Had they failed, the boundaries of India might have looked different today.

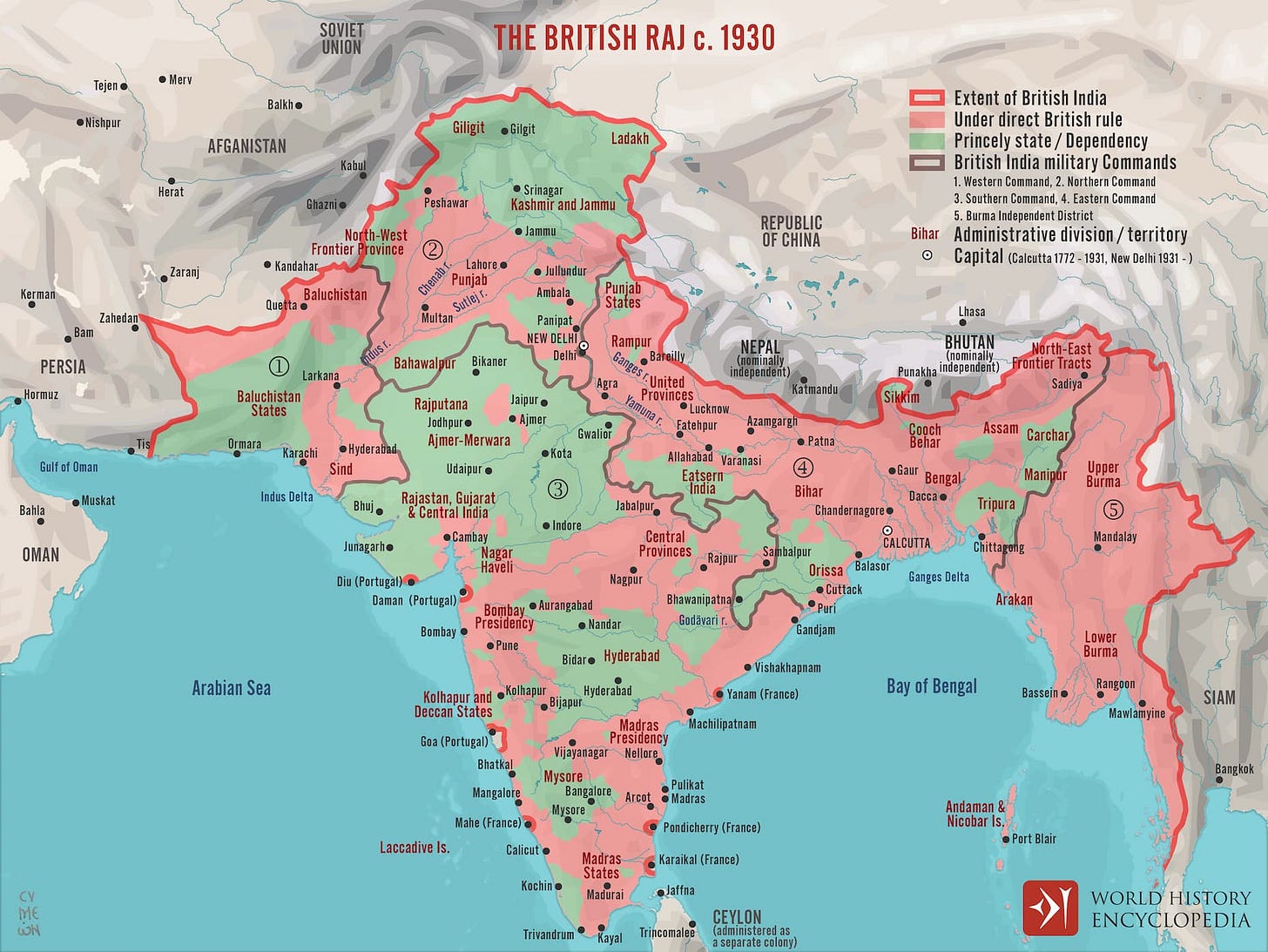

At the time, there were 565 princely states: some small estates covered less than 20 square miles, while, on the other end, Hyderabad spanned 82,000 square miles. These states were dispersed throughout the subcontinent, each having its own administration and tax collection systems, coinage, military, traditions, and customs, and were ruled by dynasties with histories stretching back centuries.

Each princely state had agreements in place between the ruler and the Crown that influenced the internal affairs, administration, and finances of the state.

Depending on the treaty, size, and military importance, some states enjoyed relative independence from British interference in their states such as Gwalior, Indore, Mysore, Travancore, and Hyderabad, while some rulers were rulers only in name, having very little autonomy.

In this edition, I want to highlight the monetary and constitutional relationship between the British Crown and the princely states in the period before India's independence in 1947.

Understanding these dynamics helps us grasp the mammoth task the leaders of India faced, in uniting this patchwork of territories into a cohesive country.

Their triumph is the ultimate story of how the pen is mightier than the sword.

This is part one of two diving into the subcontinent’s history, I hope you enjoy it❤️

East India Company: From a Company to a Coloniser

The story of British control begins with the East India Company, which laid the foundation for colonial dominance.

In 1757, the Battle of Plassey strengthened the East India Company’s foothold in the subcontinent. For the next 190 years the East India Company followed by the British Crown ruled over what is now Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar.

As a for-profit entity, the East India Company expanded its turf through negotiation and treaties. And where necessary to secure their profits, their armies fought wars.

These treaties served as protective moats for the Company's lucrative trade deals, ensuring no rival could threaten their interests.

By the early 1800s, British interests had expanded considerably, with many provinces under direct company control, while other princely states such as Hyderabad, Travancore, Mysore, Baroda, and Gwalior aligned themselves to the British through treaties.

These agreements gave the Empire leeway to interfere in the workings of the princely states, extracting wealth through various means.

Notable means to exert control included salt pricing, the right to mint ‘coin’ and administrative interference.

1. The British control of salt

The best quality salt in India was produced along the Rann of Kutch on the west coast and in Odisha on the east coast.

After the Battle of Buxar in 1764, the East India Company took control over salt production and sale in Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha, effectively controlling salt pricing in these areas.

Indians, especially Bengalis (east coast), were forced to pay exorbitant prices due to heavy taxation.

In the early 1800s, the Company signed various treaties with the Rajputana States1, who were seeking protection from the Marathas and to subdue internal resistance. These treaties allowed the Company to interfere in the state's affairs. Most importantly it gave the Company control over salt production in the Rann of Kutch region on India's western coast.

The imposition of transit duties and customs on salt sales became so burdensome that traders refused to purchase the salt, leaving a huge quantity of the Rann of Kutch’s production unsold.

To prevent smuggling from west to east, the Company established a "customs line," dividing northern India.

This was not an ordinary customs checkpoint monitored by officers; it was a thorny and tall barrier meant to protect imperial revenue.

The Great Hedge of India2 was established in the 1840s as a form of deterrence and control, part of the Inland Customs Line, which divided the Indian subcontinent until the British achieved complete control over the salt producing areas in the late 1870’s.

A formidable thorn fence, it was constructed entirely from an impenetrable thicket of native shrubs and designed to prevent smugglers from sneaking in salt from coastal areas to British-controlled states, where it was taxed heavily.

In some dry areas, the entire top layer of rocky soil had to be dug out and replaced for the hedge to thrive. It was built with prickly pear, clusters of thorny acacias and the thorny Indian plum tree. Not easy to maintain, the British kept iterating to make the hedge as formidable as they could. They dug ditches and brought in better soil. They built embankments to resist floods. They experimented until they found the best trees for each of the many climates that the hedge passed through. Eventually it grew long and tall and wide.

There were problems: white ants infested the hedge and could bring whole sections down, bush fires incinerated miles at a time, storms and whirlwinds could sweep parts of it away, locusts invaded, parasitic vines blighted the hedge, the trees died of natural causes. One section had rats living in it, and the patrol there introduced feral cats to combat them. A.O. Hume3 devoted his energy and intellect into building this monstrosity.

At its peak, the hedge stretched from the foothills of the Himalayas to the Odisha coast across parts of modern-day Pakistan and India.

Its existence was a point of pride for the British Empire, and the hedge was guarded day and night by thousands of officers.

In 1870, the British took over the saltworks at Sambhar Lake, India's largest inland salt lake, by signing treaties with the Ruler of Jaipur and Jodhpur. Prior to the Company’s takeover, the Sambhar salt was exported to every region of the country from the Indus to the Ganges under the name of Sambhar Lun. The Crown “leased” from the State the right to manufacture and sell the salt effectively monopolising the sale of salt all over India.

They could now tax salt at the saltworks itself rendering the hedge useless.

Within a century, the Company, and later the Crown, distorted the salt supply in India. Prior to British rule, India had enough salt to meet her needs. The British destroyed livelihoods by enforcing regulations and controlling who could sell, buy, or make salt. The rulers, mainly from the Rajput States, lost out on salt revenue and ceded parts of their economy to the British.

Finally, the average Indian—if they could afford salt—paid a significant portion of their income for this household staple.

The system was twisted to benefit one party at the expense of all others.

2. The right to mint coins

When the British Crown took over the administration of India from the East India Company in 1858, over a hundred Princely States were issuing coins in the name of the Mughal Emperor4.

Coins were made of gold, silver and copper. The sheer number of these coins posed a significant obstacle to trade.

Additionally, the metal content in the coins would vary from state to state. Often mints in the princely states would melt down the British coin to provide bullion for their own adulterated issues.

In 1868, bankers in Agra faced serious losses as they held in their stocks; short-weight counterfeit currencies of Gwalior, Jaipur, Bharatpur, and Bikaner. It was impossible to tell the metal weightage just by looking at it, only when it was melted could the true weight be discovered5.

Mints owners could profit by reducing the content of the precious metal.

It became risky to hold and conduct business in native currencies.

The British Government was keen to establish uniformity of metal content in currencies across the subcontinent.

This was also a means to assert superiority over the Maharajas.

The Crown began pressuring smaller Princely States to close their mints. Suppressing native mints was easier in territories conquered or ceded to British administration, such as Bundelkhand, Punjab, Nagpur, and Awadh.

With the deportation of the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah II, to Rangoon, the illusion of Mughal rule shattered. Following 1858, intense pressure was applied on rulers to replace Mughal inscriptions on their coins with the name or portrait of the Queen of England, symbolizing acceptance of British supremacy.

Understanding the change of guard, some coins, like those from the Rajput state of Mewar, bore the inscription 'Dost-i Landhan'—'Friends of London.'

The "right to coin" was deeply linked with the Maharajas right to rule over his people. The sikka was a symbol of power and prestige. Any encroachment on this right could incite revolt so the Crown did not force its agenda.

Rebel leaders considered coining money as an essential attribute of sovereignty, and therefore the first thing they did was to strike a new coin. During the Sepoy Mutiny, Khan Bahadur, a rebel leader in Bundelkhand, issued coins in the name of Emperor Shah Alam.

Larger states faced intense pressure to reduce the number of mints in their territories and accept British coins as legal tender. A notable example occurred in Bikaner in 1893 when the 13-year-old ruler Ganga Singh sat on the throne. A Crown’s Council of Regency, composed of British officers had already been established to look over the administration of the State. In 1893, the Council unilaterally halted local minting and declared British currency legal tender in Bikaner.

By the end of the nineteenth century only large states could resist the Crowns’ pressure, a notable example was Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III of Baroda.

The Baroda Rupee had a profile portrait of the Maharaja, dressed in full regalia, in Western fashion with his name and title on the coin. The Crown could not press the issue as the Baroda Rupee was of the same purity as that of the British Indian Rupee.

Furthermore, it was produced using a mechanized press, giving it a similar feel to British coins. Faced with this stalemate, the British tried a new tactic, asking the Maharaja to mint coins of a smaller size to avoid confusion with British coins. The Maharaja complied but only reduced the diameter by a few millimeters!

The Crown profited immensely from minting coins for the subcontinent, extending its control through currency management. Payments for "leases" with rulers of Jaipur and Jodhpur, taking over saltworks, and taxes collected across the subcontinent were all made in British Rupees.

What political means could not achieve, global economic conditions did. The silver crisis at the end of the nineteenth century severely impacted the minting activities of princely states. Most states could not withstand the fall in silver value and found running mints unprofitable.

By 1910, many states, including Baroda, ceased minting altogether. Only powerful states like Hyderabad and Jaipur continued issuing coins in all three metals, though gold rapidly fell out of use after World War I, leaving mostly silver and copper coins. A few states, like Gwalior and Indore, restricted themselves to copper issues.

Hyderabad was the only state to issue banknotes in 1918 with the consent of the British due to the acute shortage of silver during the First World War. Known as Hyderabadi Osmania Sicca Rupees, these notes were legal tender, issued until 1953 in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 100, and 1000 Osmania Sicca Rupees6. They coexisted with Indian currency till 1959 when it was demonetised.

In the twentieth century, strong and rich states like Baroda, Gwalior, Hyderabad, Indore, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Kutch, Mewar, Travancore mainly issued only copper coins. The wars and resulting scarcity of silver tampered down their coin issuance leaving the British India Rupee as the dominant currency.

3. The relationship between the British administration and the Princely States

Following the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, the Government of India Act 1858, liquidated the East India Company and transferred its assets to the British Crown. Several rulers and their armies had assisted the British in suppressing the rebellion, prompting a shift in policy.

The new policy stipulated that a ruler would be punished for extreme misgovernment and, only if necessary, deposed, but his state would not be annexed for his misdeeds.

As a result, the Princely States became key cogs in the British Empire, helpful in times of necessity. Yet their relationship with the British Crown was distinct from that of British India.

Constitutionally the Princely States were separate from British India. The people of the Princely States were neither British ‘possessions’ nor British ‘subjects’.

The British Parliament had no power to directly make laws for the people in Princely States. Each state's administration was accountable to its Maharaja.

In contrast, the administration of British India was answerable to the Central Indian Executive and Legislature, having British educated officers in key positions, which in turn reported to the British Cabinet and Parliament.

The Crown was a paramount power. The principle of paramountcy was articulated by Lord Reading in a 1926 letter to the Nizam of Hyderabad: "The sovereignty of the British Crown is supreme in India, and therefore no ruler of an Indian State can justifiably claim to negotiate with the British Government on an equal footing."

Subsequent years saw the initiation and development of a political and administrative system hitherto unknown to the subcontinent.

In provinces under direct British control, a regular and uniform administration was established, composed of a hierarchy of authorities with clearly defined powers and functions. This structure began at the district level and culminated with provincial Governors and the Governor-General. The administration was impersonal, as none of the offices were hereditary, contributing to the establishment of a stable government structure in British India.

The Crown's relationship with the Princely States was conducted by the Governor-General in Council, supported by Residents and Political Agents in all important States. The Political officers in the various States had comprehensive, though unwritten, authority. This starkly contrasted with the more centralized administration of British India.

Rulers of the Princely States retained the power to hire and fire officials, decide tax levels, and determine which infrastructure projects to undertake such as roads and ports within their territories. But they had limited self-rule.

Under the terms of their treaties, Princely States had to adhere to certain rules: they could not engage in warfare or conduct negotiations with other states without the Company's prior knowledge and consent. Consequently, the Princely States were politically and administratively isolated from both British India and each other.

The British Crown was the paramount power responsible for maintaining law and order throughout the Indian subcontinent and in essence could take any action to maintain peace.

This extended to deciding the succession in the Princely States.

The ruler thus did not inherit his gaddi (seat of power) by right but received it as a gift from the paramount power. Coupled with the Crown's right to regulate rulers' statuses, salutes, and confer titles and decorations, this served to bind the rulers more closely to the Crown.

The Crown often used its influence to encroach on the sovereignty of the rulers; one example being pushing for the construction of railways to facilitate the movement of opium, cotton, and other goods.

The British made decisions primarily with their interests in mind, often prioritizing infrastructure projects like railways and telegraphs that connected Princely States with British India to serve their economic and strategic needs.

Over time, the bond between the Crown and the Princely States solidified. When World War I broke out in August 1914, many rulers rallied to support the British Empire in its time of need, offering both personal services and the resources of their states. They provided men, material, and money generously, with some rulers even serving as officers in various theaters of war.

But soon there were forces at play threatening British supremacy.

Congress and the demands for Purna Swaraj

Under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian National Congress represented the common peoples growing demand for independence.

The movement gained significant momentum when, during the Lahore session in 1929, the Congress passed the 'Purna Swaraj' resolution, calling for complete independence from British rule. This resolution marked the beginning of a large-scale political movement against colonial domination.

In the 1930s, various ideas of how British India and the Princely States should interact post-independence were discussed.

In 1942, against the backdrop of World War II, Japan seemed set to win the war in the Pacific. England desperately needed Indian men and resources to turn the tides of the war. When Rangoon fell to the Japanese, and their troops spread across Burma, India’s borders were threatened. These developments made it crucial for the British to align their interests with those of Indian leaders, compelling them to take concrete steps towards addressing India's aspirations for independence.

The UK cabinet devised a long-term plan proposing that immediately following the cessation of hostilities, a constitution-making body would be established. This body was tasked with framing the constitution for a new Indian Union, comprising only the provinces of British India.

By 1946, as the Crown prepared to cease exercising its powers of paramountcy, the rulers of the princely states declared that these powers should not be transferred to a successor government, whether the Dominion of India or Pakistan. The rulers and their dewans (chief ministers) argued that the Princely States should not be compelled to join any union and should have the option to become independent.

The future of the new country appeared uncertain. The transition from colonial rule to independence posed complex challenges that required careful negotiation and collaboration among all parties involved.

The story of how Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Lord Mountbatten, and V.P. Menon—convinced, cajoled, and threatened the rulers of the princely states to unite with India will be covered in the next edition.

P.S. I got the nuances of this article from the book The Story of the Integration of the Indian States by V.P. Menon. It gives an in-depth view of the challenges faced in bringing the country together. If you enjoyed this article, you should read the book here. It is free to read.

All the articles on Filtered Kapi take a lot of time, love and care to write. It really helps boost my confidence to keep going when readers interact by liking the post or better yet commenting and letting me know what they thought about it.

Filtered Kapi #64

He later founded the Indian National Congress

To have a look at the coins of the Marathas, Awadh, Hyder Ali, Tipu Sultan look here→ Reserve bank of India

Aditi, very informative and interesting read. Sadly, we never learned such details in our history courses in India. Keep up the excellent research and writing. Thank you

These articles are really fun to read, Please keep writing. In todays time of low atfention spans,your writing style is so engaging that I could read the whole article without getting distracted.