How the British delayed giving India freedom

Examining the constitutional reforms and their impact on Hindus, Muslims and the people in the princely states

Hi there,

This is part two of a four-part series on how the Princely States were integrated with India. Please read part one here, which covers the relationship binding the Princely States with the British Crown via salt taxation, curbing their right to mint coins and administrative interference.

At the start of the last century, the British administration enacted various constitutional reforms to govern British India better. This piece covers what those reforms were, and that’s why the article is a bit technical. But to understand the journey of how India gained independence in 1947; we need to understand what reforms were tried before 1947 and why they failed.

Let's dig in.

A rising clamour for more Indians in the administration

On August 20th, 1917, Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, declared the policy of “progressive realization of responsible government in India”. Meaning more elected Indians in positions of power within the British administration system.

During World War 1, Britain had depended heavily on India’s contributions to the war effort in the form of men, material and money. The leaders of the Home Rule movement, sensing the Crown's weakness, demanded clear and decisive moves towards self-rule. To continue ruling over India peacefully, the British realized changes were needed and power had to be given to Indians. The Montagu declaration was partially a result of the pressure put by the leaders of the movement.

But how should power be given to Indians?

Diarchy - The splitting of power

In Diarchy (or Dyarchy) authority is split between two separate authorities, each accountable for a certain domain. In British India, power would be divided between British officials and elected Indian delegates.

The provincial legislative councils were expanded, with nation-building subjects like education, sanitation, agriculture, and public health transferred to elected Indian ministers. Critical sectors such as finance, law and order, army, and police remained under British officers. In case of conflict, the governor had the final say.

Dyarchy was introduced as part of Montagu-Chelmsford reforms under the Government of India Act 1919. In 1921, it was implemented in eleven provinces including Bengal, Madras, and Bombay, allowing Indians to participate in government while preserving British supremacy.

B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of India's Constitution, referred to the Act as the 'British Constitution of India' in a 1923 lecture. Many scholars view it as the first British attempt at introducing self-government in India, albeit with significant restrictions1.

Many at the time, including numerous Indians, believed Indians incapable of self-governance, citing racism, incapability, illiteracy, and religious divide as justifications for colonial rule.

The Congress declared the reforms "disappointing" and "unsatisfactory," demanding self-government instead.

However, with the imperial power controlling finances, the reforms were bound to fail. For instance, Indian ministers had no money for education schemes due to heavy levies on provincial revenues by the Central Government to repay war debts and maintain the army2.

In 1923, Congressmen led by Chittaranjan Das and Pandit Motilal Nehru formed the 'Swaraj Party' within Congress, aiming to wreck the legislatures by rejecting British proposals. The party won considerable seats in Bombay and Bengal in 1924-25, making dyarchy's functioning difficult3.

As Congress positioned itself as the people's voice, active resistance against British rule gained traction.

Teasing Dominion Status - Irwin Declaration

In October 1929, Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of India, stated the intention of granting India Dominion Status; but failed to mention any timeline4.

This status would have made India an autonomous country within the British Empire, equal in status to the UK but still maintaining allegiance to the Crown.

The declaration triggered a backlash on multiple fronts. In the British Parliament, many believed Indians incapable of self-governance. Leaders of existing Dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa) opposed equating their status with that of a non-white society.

In India, nationalist leaders welcomed the Declaration and radically changed their mode of engagement with the British government: they now wanted all negotiations with Britain to be about the formalization of dominion status for India and the framing of a new Constitution.

It seemed Lord Irwin himself intended the Declaration to not materialize any time in the near future. Indian leaders, on the other hand, felt that dominion status was within arm's reach. The Congress, irked, changed its stance: it gave up demands for dominion status and instead, in December 1929, passed the 'Purna Swaraj' resolution calling for complete independence.

This resolution marked the beginning of a large-scale non-violent civil disobedience movement against colonial rule. The follow-up Dandi March brought people together to shake off the British yoke.

Dealing with the Princely States

Butler Committee Recommendations

In 1928, the Butler Committee addressed the future of the Princely States, advising that given the historical relationship between the Crown and the Maharajahs, these rulers should not be placed under an Indian Government accountable to the people without their prior agreement.

The rulers were relieved to know there was no immediate danger to their position.

India Divided

British India was a patchwork of territories, some directly governed by the British and others, known as Princely States, managed by Indian rulers under British influence.

There were 565 princely states, varying in size from small taluks averaging an area of 20 square miles and populated by around 3,000 people to some states like Hyderabad commanding an area of 82,000 square miles, having its own coinage, and ruled by a dynasty whose history stretched back to Mughal times. Some of these smaller states provided their rulers with an annual income as low as Rs 22,000 at the time.

Each state had agreements with the British Raj affecting revenue-sharing, administration, and finances. The future of these states was to be decided in a series of Round Table Conferences starting in 1930.

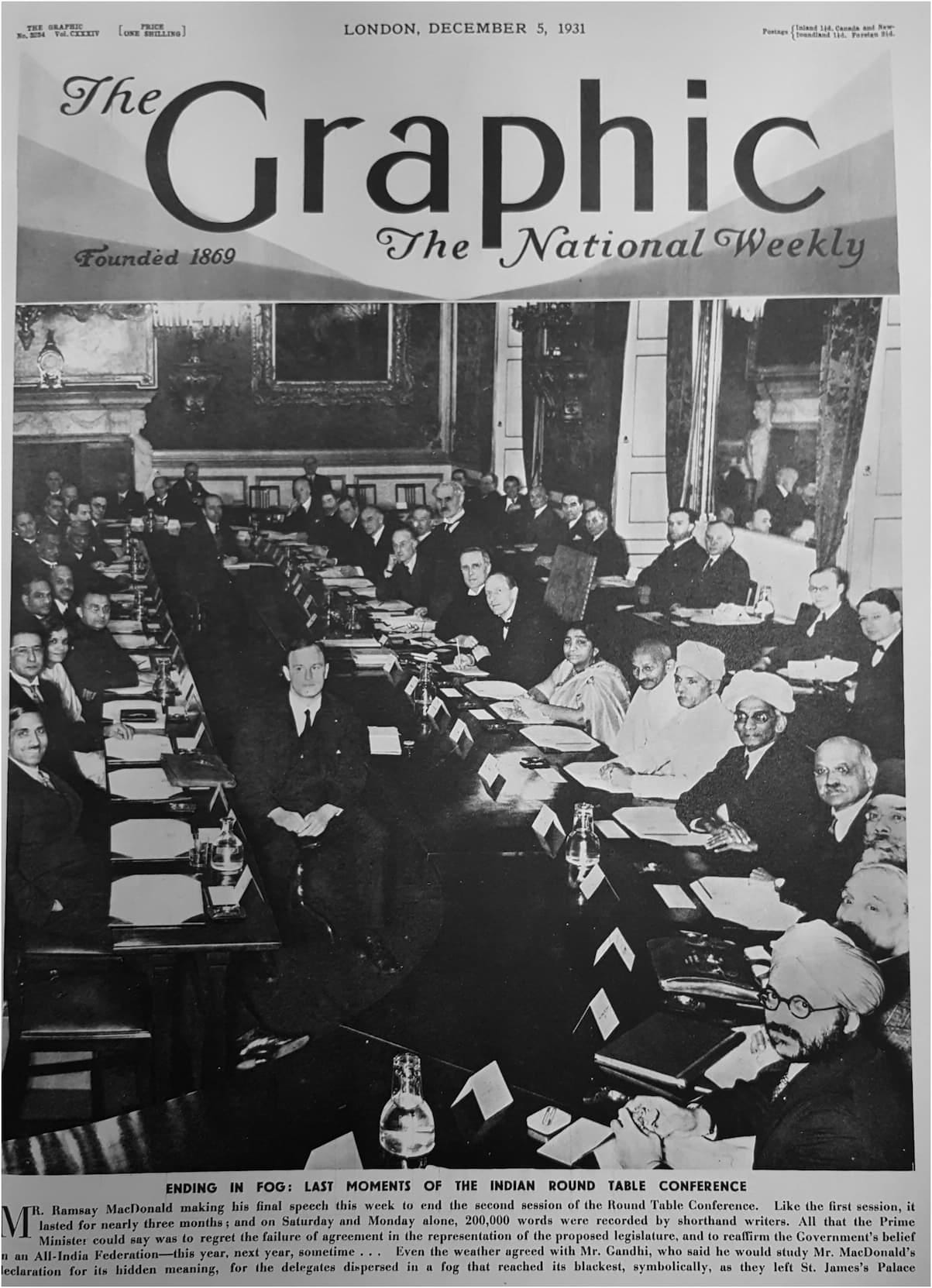

Round Table Conferences in London

In winter of 1930, the British Parliament hosted the first Round Table Conference to discuss India's future. Sixteen princely state rulers attended, but the Congress was absent as most leaders were jailed due to civil disobedience. However, other Indian party representatives were present.

On the first day of the plenary session of the Conference, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, one of the spokesmen of the delegates from British India, declared himself decisively for a federal system of government at the center and invited the rulers to agree forthwith to the creation of an all-India federation.

The Maharajah of Bikaner, the Sir Ganga Singh5, aligned himself and the princely order with the aspirations of British India and with 'that passion for an equal status in the eyes of the world, expressed in the desire for Dominion Status which is the dominant force amongst all thinking Indians today.' He agreed that India must be united on a federal basis and gave an assurance that the rulers would come in provided their rights were guaranteed.

Similarly, the Nawab of Bhopal, Sir Hamidullah Khan, went one step further and said, 'We can only federate with a self-governing and federal British India', effectively forming a common Indian front.

There were several possible reasons which prompted this response from the rulers.

No Indian was untouched by the mass awakening in British India. In some regions, disturbances occurred, and authority was challenged. Rulers were aware of the potential disaster if civil disobedience campaigns were launched in their states.

Rulers believed they could negotiate favorable terms before India united.

Some rulers thought their States would gain financial benefits by joining the federation.

A few were driven by personal ambition, looking forward to influencing administration and possibly holding high offices in the new government.

However, there was division within princely ranks on the specifics of any deal with a self-governing India. Notably, there was disagreement over the number of seats the States would have in the federal legislature of the Indian Union and their financial liabilities.

In 1933, the Chamber of Princes, a representative body of the rulers, outlined several safeguards they deemed essential before agreeing to join the federation:

Respect for Treaty Rights: The new Constitution should honor their existing treaties.

Non-Interference: There should be no interference in their internal affairs.

Collective Accession: Provision should be made for states to join the federation collectively through a confederation. This meant some states would unite under a political union to ensure fair dealings for all members, with the union acceding to a new India.

Based on the round table conferences and subsequent negotiations, the Government of India Act, 1935 ("The Act") was drafted.

Provisions of the Act

The Act aimed to establish a constitutional relationship between the States and British India on a federal basis, with the accession of the States to the federation being voluntary.6

Below are some salient features of the Act:

The creation of a Federation of India consisting of two levels: a central executive and parliament, and below it, provinces and princely states.

It discarded the Dyarchy system at the provincial level. The Act introduced responsible governments in provinces; answerable to the people. The governor was required to act on the advice of elected ministers. Legislators were now able to form majorities and take charge in local matters. However, in the event of a political breakdown the provincial governors enjoyed critical emergency powers including the power to take control of the government and remove elected ministers. This provision came into effect in 1937 but was discontinued in 19397.

The act divided the powers between centre and provincial units in terms of three lists: federal list, the provincial list and the concurrent list.

Separation of Burma, now Myanmar, from British India

Establishment of the Reserve Bank of India

It was generally recognized that the provincial part of the Act was a step forward as it conferred a great deal of power and patronage on politicians and British officials. However, the paternalistic threat of intervention by the British governor irked Indian nationalists.

Indian leaders prioritized forming a Constituent Assembly to draft a Constitution, yet the Crown refrained from discussing Independence or providing a timeline for Dominion Status. Rulers of the princely states valued their sovereignty and financial positions before committing to any agreements.

Most political parties in India took a negative view of the Act. Congress called it a ‘slave constitution that attempted to strengthen and perpetuate the economic bondage of India’. However, the Congress encouraged its members to fight in the elections under the Act, obtain positions in the legislatures, and then work towards undermining the Act. The Muslim League also attacked the Act but was ready to work with it for ‘what it was worth’.

Attempts to establish the Federation of India, as outlined in the Act, failed despite Viceroy Lord Linlithgow’s efforts. The lack of consent from rulers, who saw no urgent need or advantage in joining a Union, hindered its formation. Consequently, the Act received a lukewarm response in India due to a lack of Indian involvement in drafting, while appearing too radical to British parliamentarians.

In the meantime, the provincial part of the Act was put into operation and elections to the legislatures held in 1937. The Congress swept the polls in six provinces. This victory inspired movements for civil liberties and responsible governance in princely states such as Mysore, Travancore, Kashmir, Hyderabad, Jaipur, and Rajkot.

The onset of the Second World War shifted priorities, as the Empire required the support of rulers in terms of men, money, and materials. Ultimately, after twelve years, the concept of a federation was abandoned, marking a considerable wastage of energy and resources8

Governing in the middle of the Second World War and how it affected all parties

In protest against Lord Linlithgow's unilateral decision to involve India in the Second World War without a timeline for granting Dominion status, the Congress ministries in various provinces resigned, leading to the administration being taken over by the Governors.

At the time, the communal situation had considerably deteriorated, and no understanding could be brought about between the two major communities - Hindus and Muslims.

In 1940, Jinnah demanded a separate state of Pakistan for Muslims.

The war necessitated resources, prompting Sir Stafford Cripps to visit India in March 1942 with the goal of securing Indian cooperation in the war effort.

The Cripps Mission proposed that, after the war, a constitution-making body would be established to draft a new Indian Union constitution, offering full Dominion status with an option to secede from the British Commonwealth.9

The Congress Working Committee rejected the Cripps proposal, recognizing that the British were negotiating from a weakened position. Gandhi criticized the offer as a "post-dated cheque drawn on a failing bank." Meanwhile, the Maharajas of the Princely States realized their bargaining power was diminishing alongside the declining British influence.

In August 1942, taking advantage of the British weakness, the Congress Working Committee issued a 'Quit India' call, threatening civil disobedience unless their demands were met. In response, the British government imprisoned nearly the entire Congress leadership for the war's duration.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had long opposed Indian independence, having voted against the Government of India Act of 1935, as an MP.10

However, Sir Cripps managed to gain support from Jinnah and the Muslim League by offering them concessions.

This led Jinnah to encourage Muslim participation in the war, allowing the British to continue governing India through officials and military personnel with the League's cooperation.

After World War 2

After World War II, the Labour Party, led by Clement Attlee, won the British election.

Attlee was sympathetic to the Indian cause, recognizing the necessity of granting independence to avoid mass civil unrest and maintain Britain's global standing, especially with its ally, the USA.

This didn’t mean the British administration could just up and leave. They would have to play a role in getting all parties Hindu, Muslims, Minorities, Rulers to come together.

But they didn’t plan on keeping any troops in India and therefore would not be able to maintain internal security in the princely states as part of its treaty obligations.

By March 1946, discussions commenced regarding the process for drafting a new constitution for India.

How to bring India together?

The initial step in unifying India was to engage the princely states.

The Nawab of Bhopal, serving as the Chancellor of the Chamber of Princes, proposed a "loose" central government with residual powers remaining with the states.

The Raja of Bilaspur, a small state, believed, that each State must be allowed to regain its former independence and be left to itself to do as it wanted. He considered that the states had just as much right to independence as had British India. Bilaspur would, if need be, fight to protect itself. Incidentally, this State was less than 500 square miles in area and had a total population of a little more than a lakh11!

The rulers of small states, which number 327 averaging an area of 20 square miles, were worried about losing their sovereignty and identity by being absorbed into the Union.

The larger states also put forth their demands, Hyderabad wanted back the territories ceded to the East India Company and added a new claim for an outlet to the sea. Goa was suggested. As Hyderabad was landlocked, a port city such as Goa would enable them to import goods by rail across British India territory.

The state representatives broadly advocated for the following:

The Crown's paramountcy power should not be transferred to a successor government but should lapse.

States should not be compelled to join any Union or Unions.

There should be no interference in their internal affairs by new Indian government, preserving the rulers' sovereignty.

It’s easy to scoff at authoritarian rule today but at that time it was considered a part of the Indian heritage, culture and civilization. In some states, benevolent rulers had deep familial ties to their domains, and the populace relied on them for employment in households and armies—a traditional way of life.

Cabinet Mission Plan

In May 1946, the Cabinet Mission Plan sought to address the concerns of the princely states with the following proposals:

Paramountcy would neither be retained by the British nor transferred to the new government; leaving the states free to choose their future.

Key areas such as foreign affairs, defense, currency, and communications would be managed by the Union, while all other powers would remain with the states.

The Constituent Assembly would include appropriate representation for the states, not exceeding 93 seats.

To fill the power vacuum left by the Crown, states were encouraged to either enter a relationship with the successor government or form specific political arrangements. It also emphasized the importance of conducting negotiations with the new Indian Union to regulate matters of common interest, particularly in economic and financial sectors.

The Cabinet Mission Plan provided a framework for the new Union to follow, but the path to a unified India was complex both before and after independence.

The story continues in the next edition that I hope to have out soon.

All the articles on Filtered Kapi take a lot of time, love and care to write. It really helps boost my confidence to keep going when readers interact by liking the post or better yet commenting and letting me know what they thought about it.

Filtered Kapi #66

Discussions wrt a federation had started in the late 1920’s.

Great article. I had read about round tables, cabinet and cripps missions but only today I understood the proposals and objectives of each. Looking forward to the next articles in this series.

Loved the piece! The fact that the Bilaspur with 100,000 people was willing to fight for their right to not be absorbed was eye opening to me. They maharajas really valued their independence and autonomy. Can't wait for the next one.