Hi there,

This story explores the blunders made by the French nobility and bureaucrats in managing their economy.

The mismanagement destroyed the public’s faith in the King and determined France's fate in its future wars against arch-rivals England.

I love the intersection of history and money and hopefully you do too, or you will after reading this story.

For brevity and my sanity, I have divided the story into two parts.

This section examines French society and social norms, highlighting how the societal structure was built on oppressing a segment of the population. The resulting divide led to the fermenting of a revolution.

Let's go.

Let them eat cake?

The French monarchy were notorious spenders. They consistently spent more than they received from levying taxes, with the shortfall financed by borrowings.

The Crown had many expenses to bear one of them being managing La Maison du Roi, the royal household. Steeped in traditions and legacy the system required a vast number of people to ensure the King's day was managed to perfection.

The household comprised of three parts:

Dedicated Military Units: These elite troops served as both the sovereign's bodyguards and soldiers during wars. On the battlefield, they protected the monarch. The King's military consisted of officers and commoners, divided into cavalry and infantry units.

Domestic Entourage: A large staff of attendants, chamberlains, esquires, chefs, and aides were organized under various departments responsible for the King's daily life. Their duties included:

Providing food and drink

Managing rooms and chambers

Overseeing clothing

Organizing entertainment and events

Maintaining silverware and lighting in palaces

Managing ceremonies

Overseeing royal stables and hunting expeditions

Here is a snippet to illustrate the intricacy of court life,

At the coronation banquet, once the king gave the order for the meal, the grand maître informed the king that the table was set. The panetier (breadmaster) fetched the king's napkins, the échanson (cupbearer) brought glasses and flasks, and the tranchant (carver) carried the knife, fork, and spoon. During the meal, the grand maître stood at the King’s right side. The panetier changed the king's napkins and plates, the échanson served wine, and the tranchant handled the dishes1.

Religious Attendants: The Grand Aumônier served as the king's pastor, attending to the monarch's morning and evening prayers and meals to say grace. He and his subordinates administered sacraments to the king, baptized royal children, and officiated the marriages of princes.

This elaborate structure came at a significant expense, further burdened by the royalty's lavish lifestyle.

Music and Entertainment

At the French court, music was an essential part of daily life and grand ceremonies, serving both political and entertainment purposes. The monarchy maintained a dedicated musical corps as part of the royal household, which entertained the King with the latest musical acts.

Financial Turmoil and Attempts at Reform

By the 1750s, the accumulated debts had reached astronomical levels, leading many to question the Crown's ability to repay its loans.

Despite the monarchy's extravagant spending, it wasn't a cause for alarm. The economy was growing faster than the interest burden, and the Crown had both the intention and ability to repay its debts.

However, a significant problem lay in the Crown's secretiveness about its finances. This lack of transparency prevented creditors and taxpayers from understanding the complete financial picture, ultimately contributing to a crisis of confidence.

The Financial Implosion of 1769

The troubles escalated in late 1769 when the Crown was forced to declare a partial default on the country's debts. Over the decades, they had borrowed heavily to fund wars and maintain the grandiose lifestyle their forefathers had established. With each new loan it became more expensive to borrow.

It's important to recognize there was no distinction between the kingdom's debts and the king's personal debts. As Louis XIV allegedly proclaimed before the Parlement de Paris, "L'État, c'est moi" (I am the state). Whether he uttered these words or not, they encapsulated the reality of the king's absolute power. Under Louis XIV's reign, power was centralized under the throne, sidelining other powerful noble families who might have provided checks and balances.

This concentration of power was rooted in the belief that God had endowed the King with a divine right to rule. This ideology further complicated attempts to separate state finances from royal expenditures.

The default shook the foundations of French administration and finances.

Reforms and their impact

In the wake of the financial crisis, various reforms were implemented:

Pensions were cut

Various tax exemptions were eliminated and new taxes introduced

Interest rates on government debt were unilaterally slashed while payments on some loans stopped.

Offices held by members of the royal household were reduced2

While many creditors of the Crown were bitter, some, including the writer Voltaire, who had lost 200,000 livres, a hefty sum, believed that the crunch had been inevitable.

Over time, these reforms began to take effect. The Crown managed to shrink its outstanding debts, which helped restore the monarchy's credit to some degree.

A Teenage King

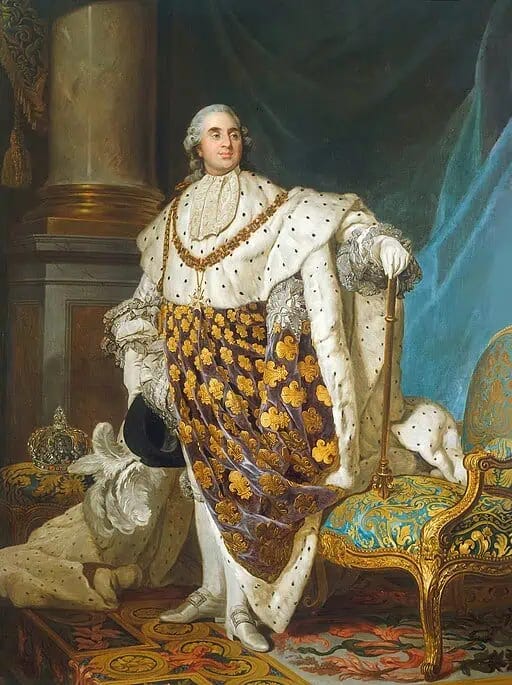

In 1774, at the age of 19, Louis XVI ascended the French throne. Originally not groomed for the role, he was thrust into the limelight following the untimely death of his older brother and the passing of his grandfather, King Louis XV.

Louis XVI was a shy monarch, preferring quiet evenings with a book by the fireside to the pomp of court life. He indulged his interest in the applied sciences and the latest technical and mechanical curiosities. This included spending time in workshops devoted to physics, mechanics, chemistry, watchmaking along with a working forge and a room for experiments involving electricity.

Left to his own devices, Louis was drawn to solitary pursuits like lock-making and carpentry. Another of his great passions was hunting.

His library boasted 8,000 meticulously arranged leather bound volumes. Louis XVI was well-educated and continued to pursue learning as king. He read widely, including philosophy, political thought, history, and fiction—Robinson Crusoe was among his favorites3.

Despite his position, he stood for progressive policies such as the abolition of serfdom, increased religious tolerance, and reduced taxes on the poor. He also supported the American Revolution, hoping it would weaken the British Empire.

The Legacy of Louis XIV: The Estates System

Louis XVI inherited a system of governance that was fundamentally dysfunctional.

His ancestor, Louis XIV, had centralized authority and established France as a major European power. But this consolidation forced a medieval societal structure that would prove problematic.

French society was rigidly divided into three estates:

The First Estate: The Clergy

The First Estate comprised all members of the Catholic Church, estimated to be 0.5% of the total population. The clergy held a vital position in French society, acting as the sole supreme religious authority. It was divided into two groups:

The 'higher clergy' consisted of noblemen holding high-ranking positions of influence such as archbishops, bishops, cardinals, the Grand Aumônier (the king's pastor), the king's confessor, and the king's preacher.

The 'lower clergy' included parish priests (curés), friars, monks, and nuns, mostly originating from the Third Estate.

The First Estate performed various functions, such as facilitating weddings and funerals, providing education to children, and administering charity to the poor.

Despite owning roughly 10% of French land, the Church was exempt from paying direct taxes. This exemption helped build generational wealth, allowing the clergy to accumulate significant resources.

However, there was a considerable divide in terms of wealth and income within the First Estate:

The higher clergy were seen as living opulent and indulgent lifestyles, disconnected from the hardships and ground realities of the people they were supposed to guide. The perception was that they often redirected Church funds for their own use.

In contrast, parish priests were often looked down upon by the elitist higher clergy and were poorly compensated by the Church.

This disparity led to divisions within the clergy.

The Second Estate: The Nobility

Representing aristocrats, they consisted of less than 2% of the population but owned 20% of the land. Like the First Estate, they did not pay direct taxes. The nobility held a chunk of wealth and dominated key official posts, such as:

Ambassadorships

Military commands

High ranks in the judicial system

Police

Tax collection

The king's household

These positions provided them with access and influence in public service. However, this came at a cost.

Venal Offices

The monarchy sold positions, known as "venal offices", to raise money. Louis XIV, in his time, sold such offices during the War of Spanish Succession. These offices could be passed to the holder's successor and would be discontinued once the initial capital was repaid.

The appointee deposited a sum of money as a form of bond for the office, making the King their debtor. The "wages" paid to the holder of office were minimal because the money was more like interest on borrowed capital, which would be paid until the capital was returned—a process that didn’t have a confirmed end date so it could be infinite.

Holding a venal office offered stable year-on-year returns, but it might not always make financial sense due to the low return on investment. As Pontchartrain (minister of Louis XIV) put it, "Every time the king created an office, God created a fool to buy it."

Investment and Wealth

At that time, there were three major asset classes where wealth would be invested:

Land

Assets loaned out for income

Venal offices

A study of French private wealth in 1787 showed the following breakdown:

Land being exploited: 80%

Houses rented: 10%

Governmental perpetual and lifetime bonds: 4%

Venal offices: 2.5%

Acquiring and maintaining an official position required significant wealth. It was expensive to uphold the lifestyle expected of an official, necessitating income from other sources.

Despite the costs, there was demand for offices as they offered upward social mobility for commoners.

If an office was held for three generations, the third-generation officer's family would be considered nobility, becoming part of the Second Estate and exempt from taxes4.

The sale of venal offices increased markedly during the 1700s. These venal offices did not come cheap. A minor office could cost 20,000 livres while higher offices with immediate noble status were in excess of 50,000 livres. Most were merchants who acquired wealth from France’s booming imperial trade. Others made their fortunes from colonial investments, banking and finance or tax farming5.

During the eighteenth century, the monarchy made half-hearted attempts to cull some offices, but poor money management hindered these efforts.

The state had delegated its power, and the officer’s performed roles that, in today's age, the state would fulfill, such as judges, police, and tax collectors. Although these offices were an extension of the king's authority, they were essentially sold to the wealthy, which did not guarantee that the officeholders were capable or efficient at their jobs. This system became a means for rich families to control the people in their territories.

Seigneurial Rights

Depending on the office, some noble families had bespoke rights. These varied greatly in nature and often caused resentment towards the aristocracy. Examples include:

The right to a monopoly on the bread oven for the village

Exclusive rights to presses for processing olives and grapes in their region

Public Perception

Many commoners perceived the Second Estate as indulgent, unproductive, and disconnected from reality. Gossip and libels highlighted the excesses of the court in Versailles, amplifying stories of sexual promiscuity, gambling, court intrigue, and other actions deemed immoral in the 18th century. Cultural depictions also painted the nobility as hedonistic, indifferent, or even cruel to others.

This led to a widespread perception that the nobility played while the commonfolk worked.

It's important to note that the material wealth of the nobility varied dramatically. While the nobles who resided at court were famed for their excessive wealth and lifestyle, many members of the rural nobility were relatively poor. This led to resentment against the monarchy for failing to protect failing to protect their privileges6.

The Third Estate: The Commoners

The Third Estate represented the overwhelming majority of the French population, including:

Wealthy urban elite

Merchants

Skilled craftsmen

Illiterate peasantry

Members were required to pay a variety of taxes and dues:

Direct taxes

Indirect taxes

Seigneurial dues

Tithe (a percentage of income) to the Church

The Third Estate bore the brunt of France's financial burdens. This disparity in financial responsibility, coupled with their lack of political representation, placed an enormous strain on the common people.

As the 18th century progressed, this imbalance became increasingly unsustainable. The stark contrast between the privileges enjoyed by the clergy and nobility and the mounting pressures on the Third Estate created a powder keg of social tension. The inequities inherent in this rigid societal structure would ultimately prove to be a significant catalyst for the sweeping changes that would come.

The need for more money

During 1775, the American War of Independence began.

Motivated by their desire to humiliate the British, the French provided essential support in many forms, including covert supplies of war materials, personnel, diplomatic backing in Europe, and eventually, a full-fledged military alliance.

This support made American victory a possibility but put further strain on the limited French treasury.

The war-related expenditures were financed entirely through borrowing, made possible by Swiss banker Jacques Necker's credibility with creditors. Appointed as director general of finance, he had virtual control over French finances. This was a considerable feat just six years after the 1769 bankruptcy, and it was achieved without raising taxes.

Necker instituted reforms and dissolved many of the venal offices, resulting in immediate savings of 84.5 million livres.

Necker's strategy of raising funds through life annuities sparked a financial bubble that crippled the monarchy and plunged French finances into chaos for decades.

I will cover this in the second part, which will be posted next week🤞

P.S. I had fewer grey hairs when I started writing this edition. This newsletter took a lot of ruined weekends. If you've made it this far and enjoyed it, I would really appreciate it if you could share, like, or comment! Your support motivates me to keep writing, as sometimes I find it hard to believe anyone really cares. Thanks for your attention!

Filtered Kapi #60

Read more here→ “Was There a Solution to the Ancien Régime's Financial Dilemma?” by Eugene Nelson White to get an overview of French problems during the late eighteenth century.

Read more about Louis here→ The Human Side of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

Music was an integral part of routine life; Queen Marie Antoinette was passionate about music. She sang and played the harp and harpsichord. At her private music salon, in the Petit Trianon, a château located on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles, she arranged for a miniature theatre to be constructed where she performed fashionable operas for her close friends. This allowed her to escape the rigid court etiquette and indulge in her love for the arts.

The Queen had lavish tastes, which included buying over 200 new dresses per year, exemplifying the perception of the Crown being indulgent.

This is a really ambitious project, Aditi. Tremendous effort to distill all the research it must've required into such a simple and fluid narration. Great stuff!

Absolutely loved reading this Aditi. Can't fathom the amount of efforts it must have taken, but this ended up being a really informative and a fun read.

I am always on the lookout for content which explores history and economics through a common lens - would it be possible for you to do a post on things you recommend reading/watching/podcasts you follow?