From Annuities to Anarchy: How Fiscal Mismanagement Fueled the French Revolution

Exploring the various methods of financing used to avoid a bankruptcy and its impact on people

Hi there,

Welcome to the second installment of our series exploring the financial causes behind the French Revolution.

In case you missed it, do read the first part of this story here. It examines the rigid structure of French society and the resulting resentment against the status quo.

This edition focuses on how French finances continued to degrade to the point of revolution.

Let’s go.

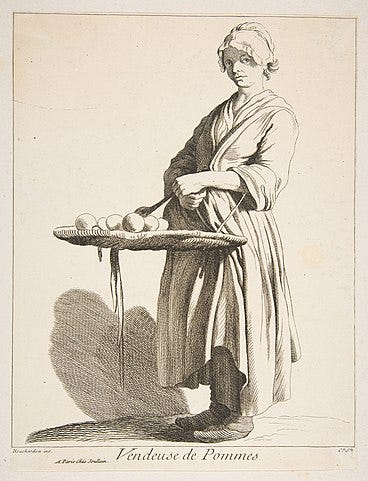

A day in the life of a French citizen

It’s hard to empathize with people from centuries ago without understanding their lives. Luckily, Arthur Young’s writings give us a glimpse.

Young was an English travel writer who toured France exploring agricultural practices.

The below excerpts are from his book "Arthur Young's Travels in France during the Years 1787, 1788, 1789"; the words in brackets are mine.

On 25th September 1787, he talks about the streets of Paris:

This great city appears to be in many respects the most ineligible and inconvenient for the residence of a person of small fortune of any that I have seen; and vastly inferior to London. The streets are very narrow, and many of them crouded, nine tenths dirty, and all without foot-pavements. Walking, which in London is so pleasant and so clean, that ladies do it every day, is here a toil and a fatigue to a man, and an impossibility to a well dressed woman. The coaches are numerous, and, what are much worse, there are an infinity of one-horse cabriolets (one-horse carriage), which are driven by young men of fashion and their imitators alike fools, with such rapidity as to be real nuisances, and render the streets exceedingly dangerous, without an incessant caution. I saw a poor child run over and probably killed, and have been myself many times blackened with the mud of the kennels.

[…]

This circumstance renders Paris an ineligible residence for persons particularly families that cannot afford to keep a coach; a convenience which is as dear as at London.

[…]

To this circumstance also it is owing, that all persons of small or moderated fortune, are forced to dress in black, with black stockings; the dusky hue of this in company is not so disagreeable a circumstance as being too great a distinction; too clear a line drawn in company between a man that has a good fortune, and another that has not.

On 14th October 1787, in Paris he talks about the salary paid to the clergymen.

To the benedictine abbey of St. Germain, to see pillars of African marble, &c. It is the richest abbey in France: the abbot has 300,000 liv. a year (13,125l.) I lose my patience at such revenues being thus bestowed; consistent with the spirit of the tenth century, but not with that of the eighteenth. What a noble farm would the fourth of this income establish! what turnips, what cabbages, what potatoes, what clover, what sheep, what wool!—Are not these things better than a fat ecclesiastic?(member of the clergy)

On 5th September, 1788 at Mountauban-de-Bretagne located in northwestern France

The poor people seem poor indeed; the children terribly ragged, if possible worse clad than it with no cloaths at all; as to shoes and stockings they are luxuries. A beautiful girl of six or seven years playing with a stick, and smiling under such a bundle of rags as made my heart ache to see her: they did not beg, and when I gave them any thing seemed more surprized than obliged. One third of what I have seen of this province seems uncultivated, and nearly all of it in misery. What have kings, and ministers, and parliaments, and states, to answer for their prejudices, seeing millions of hands that would be industrious, idle and starving, through the execrable maxims of despotism, or the equally detestable prejudices of a feudal nobility

These firsthand accounts paint a stark picture of the hardships faced by the common people, making it clear why reforms were desperately needed.

Riots over Bread

While common people struggled, the French government grappled with its own financial woes.

After the 'Flour War' bread riots of 1775, King Louis XVI appointed Jacques Necker as Director-General of Finances in 1777.

This appointment coincided with France's support of the American War of Independence revolutionaries, further straining the treasury.

How a Protestant, a foreigner, and a commoner came to control French Finances

At 15, Necker left Geneva to work as a bank clerk in Paris. Soon, his punctuality and discretion earned him notice, and he spent his free time expanding his knowledge.

One day, Necker covering for an otherwise engaged chief clerk, made a series of trades contrary to his superior's instructions. The result was a swift profit of half a million French livres. This bold move propelled him to chief clerk and, eventually, partner at the bank.

Over time, Necker amassed a princely fortune of 6 million livres1.

Necker built his reputation as a political economist by publicly articulating and defending his opinions on corn laws and previous finance ministers’ actions. In 1776, his experience in international banking and reputation as a pragmatist made him an ideal candidate for the post of finance minister.

Confident in his skills, Necker was determined to pay the French creditors while ensuring the Treasury had enough funds to support the American War of Independence.

How much would you pay for a “head”?

One of the main methods to raise funds in the 18th Century was issuing Rentes viagères (life annuities). This was a well-established practice; annuities had financed multiple wars in previous decades. However, this time it was slightly different.

A life annuity is a loan contract whereby the lender transfers a lump sum in exchange for periodic payments until the death of a designated individual, called the tête or nominee. The nominee and lender/holder of the annuity can be different people. The longer the nominee survives, the more the investor earns.

The twist was that from 1761 to 1787, the state offered flat-rate life annuities, meaning the payouts were constant regardless of the nominee's age, sex, or health. Typically, annuity rates depend on the nominee's age. However, the State was so desperate for funds that it offered these illogical annuities.2

This loophole led many lenders to designate young, healthy individuals as nominees. While this expanded demand for French government debt, it significantly increased the Treasury's financial burden.

On whose “head”?

To drum up purchases of the annuities, Necker offered 10% on one “head” (nominee), 9% or 8.5% on two, and 8% on three or four “heads”3. The coupon for multiple nominees was lower as the probability of all nominees dying early was lower, hence lower return.

Genevan bankers pioneered financial innovations by forming syndicates like the “Thirty Maidens of Geneva”. These syndicates bought 30 annuities on selected nominees, pooling them together. Initially, they chose girls over seven to avoid smallpox deaths. After the success of vaccinations in 1774, they lowered the age to four, targeting wealthy families who have access to better living conditions for healthier nominees. Girls were preferred over boys because as per statistics they lived longer. Syndicates would employ doctors to draw up the initial shortlists of healthy girls4.

Investors also bought annuities on prominent figures like Louis XVI, Frederick the Great, and Marie Antoinette. These choices were strategic: the health of these individuals was reported in newspapers, and they had access to the best healthcare and living conditions, ensuring longer payouts.

Debt and Transparency: The Dual Legacy of Necker

During Necker's tenure, 530 million livres of new debt, mainly life annuities, was issued. An average annual interest charge of 8.3% added 44.4 million livres to expenses.

The new loans added further strain on the already indebted State, and the American War imposed an additional burden of 1.5 billion livres.

Necker worsened the situation by spending future revenues. He persuaded tax collectors to part with future tax revenues. These collectors, doubling as financiers, charged the State exorbitant interest rates for providing an advance on the estimated future tax revenues5.

The Treasury did not make expenditure forecasts and had vague knowledge of its revenues, while poorly tracking cash flow, even though it was involved in every revenue source. When faced with shortfalls, it scrambled to meet commitments, often resorting to hasty, ill-conceived solutions.

On the positive side, Necker increased state revenues by 25-30 million livres a year by reducing the number of tax collectors, eliminating unnecessary venal offices, and improving tax collection efficiency.

Trusted by the people

But the commoners implicitly trusted him,

As a self-made commoner, Necker resonated with the public as an expert who earned his fortune through hard work, not inherited privilege.

Necker financed a war without raising taxes, unprecedented in French history.

In 1781, Necker published the “Compte Rendu Au Roi”, a groundbreaking report that publicly disclosed the Treasury’s income and expenditures for the first time. This transparency was unprecedented in an absolute monarchy where finances were typically secret. The report revealed pensions to certain nobles and other largesse by the King, funded by money from creditors and commoners. The scandal was so significant that the report sold 200,000 copies and was quickly translated into Dutch, German, Danish, Italian, and English.

The people believed in him, but the privileged class hated him partly because he was a Protestant and because he culled venal offices, sought to control their expenditures, and made their earnings public. Partly due to the scheming of the King's council, Necker was removed from office in 1781.

In the two years after Necker’s dismissal, France had two Controller-Generals of Finances who made unpopular moves. Neither had the impact that Charles Alexandre de Calonne did to push France closer to revolution.

The Calonne Era: Troubles Multiply

Calonne became Controller-General of Finances in 1783. Before this, he served as a venal officer, holding the coveted position of Intendant of Finance, managing financial matters for Franche-Comté. Under Necker, Calonne witnessed significant changes in the government's financial structure.

Calonne had an unorthodox approach to establishing state credibility. He believed that if the Treasury spent without restraint, people would assume it was financially stable and lend freely. He treated the court lavishly and undertook public works, believing this expenditure would cause business to thrive. He restored venal offices and sought popularity by suppressing some indirect taxes6.

Calonne's remedy for the crown's financial problems was to stimulate the economy. He increased trade freedom within France, raised the number of free ports, and began negotiating a new trade treaty with England. However, there was no time for long-term incremental reforms to take hold.

According to Calonne's accounting, he borrowed 650 million livres under extremely burdensome conditions.

Expenditure grew while revenues stagnated. Despite this, Calonne continued to borrow. In 1786, he had to inform the King of an annual deficit of 101 million livres.

His proposed reforms included universal land taxation, but the Parlement would not consider any tax increases during peacetime.

Things worsened as a financial bubble formed, setting the stage for revolution.

Why did people lend money to such a risky debtor?

The answer lies in the details of this bubble's formation and collapse, which will be explored in the final part of this series, coming soon.

Filtered Kapi #61

Read more here wrt France’s economic woes→ The Paris Bourse on the Eve of the Revolution, 1781-1789 by George V. Taylor

Ibid