What happens when a Labourer can't afford bread in Pre-Revolutionary France?

The road to killing a dynasty is paved with high food prices, unfair taxes, & rampant speculation. What was the cause of this chaos?

Hi,

This edition explores the circumstances which drove French citizens to revolt in 1789.

Today, we have checks and balances to limit State power. However, back then these safeguards were lacking, and institutions were working against the nation's long-term interests.

This is the third and last part in this series. If you missed the first two, please read the first part here and the second part here.

While writing and researching this article, I was reminded of a quote by James Baldwin from his book “Notes of a Native Son”,

“People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.”

For me, this quote captures the essence of the article.

Let’s go.

In 1786, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, then the Controller-General of Finances of France, reported an annual deficit of 101 million livres to King Louis XVI.

However, a deeper problem was brewing: a financial bubble, the implosion of which would set the stage for the Revolution.

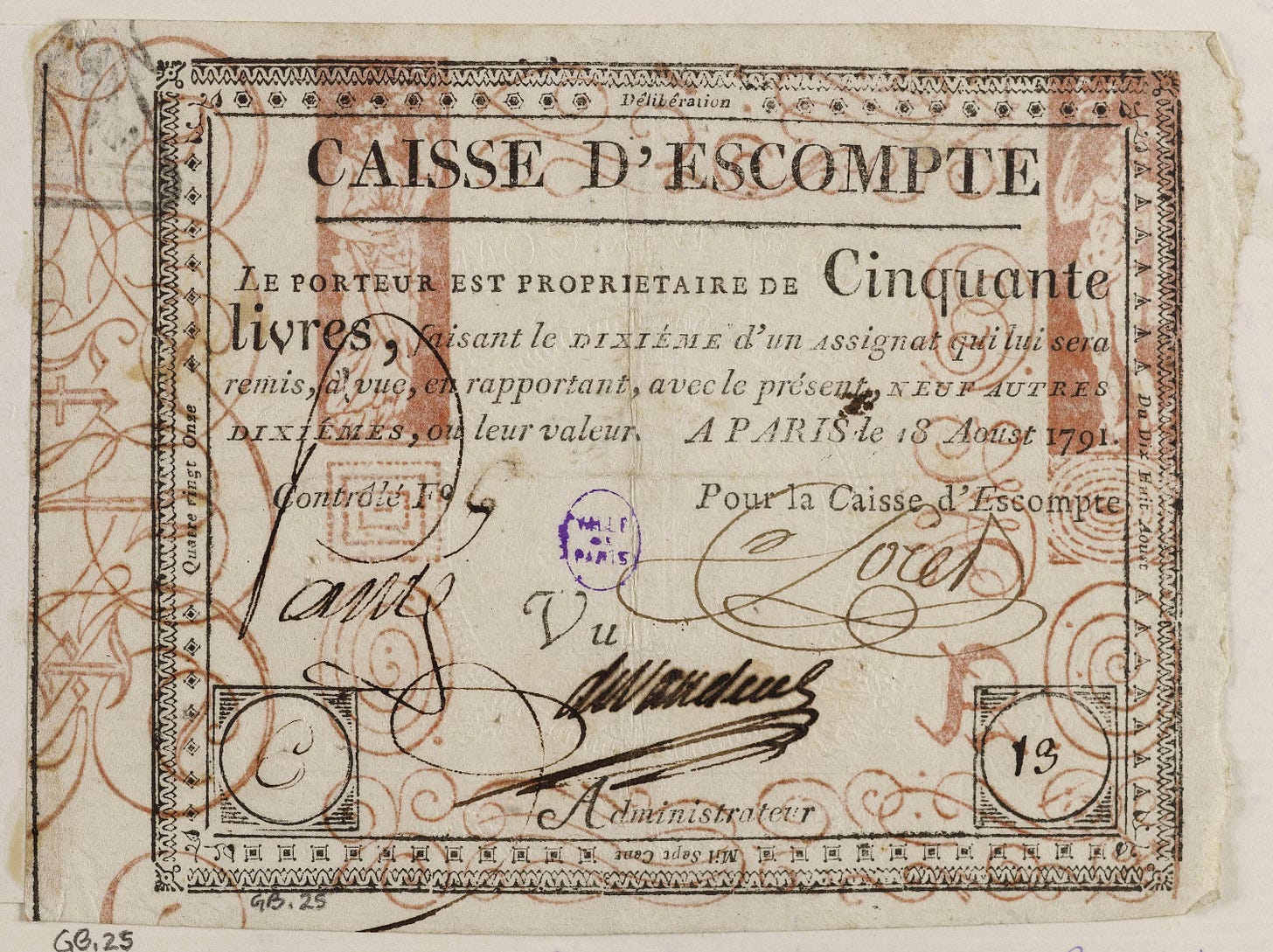

It started with a bank: the Caisse d'Escompte.

The building block of trouble: Increasing the money supply

The Caisse d’Escompte, or Discount Bank, was established in 1776.

The Caisse’s main revenue stream was discounting commercial bills. It had a 4% p.a. discount rate for 30-day bills and 4.5% p.a. for 30 to 90-day bills.

If a businessman (X) provided $100 worth of services to another party (Y), who promises to pay within 30 days, X could take the invoice to the Discount Bank and be paid $99.67 ($100 - $0.33) immediately. After 30 days, Y would pay the bank $100.

The hope was that by increasing liquidity, the Caisse would reduce the friction of doing business. While also easing France’s money constraints.

It accepted deposits, discounted Treasury loans, provided direct loans to both the Treasury and the public, and acted as the Treasury's last-resort banker.

In 1777, a year after its establishment, the bank obtained the right to issue banknotes, circulation of which was limited to Paris1.

Before these banknotes, money was held in the form of gold or silver coins, known as "specie."

A trustworthy note-issuing bank could,

Encourage transactions by reducing reliance on scarce gold/silver resources.

Issue stable-value banknotes; a 100 livre note today could buy 100 livre worth of goods tomorrow, encouraging people to use and save assets in paper currency.

Encourage borrowing by artificially lowering the interest rate to boost growth. The 4% limit was pre-determined.

To convince the public to move away from specie and trust in paper currency, the bank was well-funded, with enough metal coins in reserve to ensure convertibility and avoid a bank run2.

For a while.

A twisted relationship with the Government

The problem originated in its relationship with the Government3.

Funded with private capital but operating within an authoritarian regime, the Caisse d'Escompte required the King's approval to conduct banking operations.

The King's State Council signed the bank's charter at Versailles, with the monarch in attendance. It operated in a grey area where it wasn’t State-owned but was part of the public credit and money organization.

The discounting business was profitable and growing quickly, but the bank's fate was intertwined with its biggest debtor, the State.

In 1778, it increasingly started to discount government-issued loans, supporting the Treasury's fundraising efforts.

Soon finance ministers Necker and Calonne started demanding that the bank give loans to the State - again and again.

By the end of 1789, there were 129 million livres of banknotes in circulation, vis-à-vis only 5 million livres in precious coin left in reserve. At this point, the Caisse's banknotes had become worthless paper (fiat money)4.

However, the State still continued to require new advances, drawing out more banknotes. By December 1790, 400 million livres notes were in circulation.

Suffice to say, the trust in the banknote had eroded along with the belief in the Treasury to manage the country’s finances5.

Why were people giving their hard-earned money to a bad debtor?

Since 1777, the State relied on borrowed money. What sustained this illusion? It could be any of the below reasons:

1. Faith in the King and the land’s natural bounty

The French public adored their king. The Bourbon dynasty had ruled France for two centuries, shaping it into a world power. Unlike his predecessors, Louis XVI was perceived as a kind man, free from excesses, mistresses, and extravagant parties.

The country's problems were attributed to greedy bankers allegedly trying to weaken France, corrupt finance ministers, and venal officers mismanaging the state. Queen Marie Antoinette became a scapegoat due to her Austrian heritage (France's long-time enemy) and her lavish lifestyle.

France had abundant rivers and streams that supported agriculture, industry, and human consumption.

Despite omnipresent signs, it was hard to anticipate black swan events.

2. Belief once the American War ends the budget would be balanced

The War started in 1775 and ended in 1783. The message to creditors and taxpayers was that the borrowing would taper down once the war ended, and revenues, including taxes, would increase over time to pay off the debts.

Monitoring the true financial health was likely difficult with haphazard borrowing and repayments.

3. Frenzy in the Capital Markets making people believe the state of finances was better than it actually was

The increased money circulation gave people access to cheap credit, which went into speculating on government loans.

It was the perfect storm. The speculators were responding to the Treasury’s incentives.

Capital was plentiful from the Caisse d'Escompte and soon overseas bankers from Amsterdam, Geneva, London, and Genoa joined in. The increased activity led to frantic trading in the Paris Bourse6, particularly on life annuities.

The Allure of the Life Annuity

The marketability of life annuities (Rentes viagères) increased when it became possible to buy annuities on prominent figures like Louis XVI and the Thirty Maidens of Geneva.

This strategy allowed investors to:

Borrow capital at 5%.

Use the purchased annuities as collateral.

Repay the loan from the annuity income over 15 years.

Enjoy an 8-10% revenue for the rest of the nominee's life7.

The Evolution of Annuity-Based Loans

This cycle of borrowing and speculation was fueled by the introduction of loans offering annuity purchase options.

In 1777, Necker structured a loan of 20,000 notes of 1,200 livres each (24 mn). These notes bore no direct interest. The return would be determined by lottery. Each note had a lot drawn.

As decided by lottery, 15,000 notes would be converted into straight 4% loans. The balance 5,000 notes conferred the right to buy annuities on any nominee. The interest varied from 150 to 50,000 livres per year per note for the nominee’s lifetime.

The poorest of these yielded 12.5% and the best 4,166% for every year the nominee survived. Since one out of four notes had an annuity option, speculators bought all the loans in 24 hours8.

The bubble builds

The demand for annuities was so high that the interest was reinvested in new annuities. The Treasury would pay off a loan and simultaneously offer a new loan for investors to invest their proceeds.

These lottery-based annuity loans destroyed the country but enriched the smart speculators.

The annuity loans were issued multiple times under Necker and Calonne. Each time millions were borrowed under a crippling interest burden. To ensure they were able to borrow, the Treasury kept making the terms more attractive. This was short-term thinking with no regard for the accumulating future liabilities.

The State became beholden to its creditors and bankers. Something had to give.

Were there any avenues left to borrow from?

Increasingly large amounts of money were needed to pay off old debts, war expenses, and to keep up with the image of a healthy thriving country.

Having exhausted all external borrowing avenues, the Treasury turned its eye inwards, could it force citizens to pay more taxes?

The impact of taxes on farmers’ livelihoods

Agriculture accounted for 75% of the national product. Farmers and commoners who constituted the bulk of the Third Estate bore direct taxes.

They were taxed by the Taille, an onerous and arbitrary direct tax.

Every year, the King’s Council would decide the total sum to be collected according to the needs of the moment, and then divide it across the country. The tax collector’s role was to fulfill his quota. But since he didn’t know the taxpayer’s earnings or what they could afford, he had to rely on appearances.

Taxpayers benefited from appearing poorer than they were.

To maintain this facade,

“they [the peasants] did not dare to procure for themselves the number of animals necessary for good farming; they used to cultivate the fields in a poor way so as to pass as poor, which is what they eventually became; they pretended that it was too hard to pay in order to avoid having to pay too much; payments that were inevitably slow were made still slower; they took no pleasure or enjoyment in their food, housing or dress; their days passed in deprivation and sorrow.9”

Various indirect taxes, including the salt tax, customs duties, tolls, and octroi, impeded the free circulation of commodities and hampered the movement of goods.

The system suffered from two major flaws:

Inefficient and unequal tax collection.

The way the Taille was collected encouraged peasants to appear poorer and limit production.

It became impossible to make the French pay more because the First and Second Estates refused to pay more10, and the Third Estate already found it difficult to survive on the existing level of taxation.

Why couldn't the King force the clergy and nobles to pay direct taxes?

Once a method is established, it’s hard to change the status quo.

The Parlement de Paris blocked any reforms threatening their privileges.

The Parliaments were former law courts originally limited to registering new laws decreed by the King. They were composed of high-ranking clergy and aristocrats, neither appointed nor elected, and did not concern themselves with public interests.

Their role morphed, and in the absence of genuine representation, they acquired the power to oppose laws they disapproved of. While the King could still issue a decree, this procedure was unpopular. Public opinion regarded the Parliament as a shield against the King’s absolute authority.

The elite bent this power to serve their interests. Even on the eve of the Revolution, they refused to pay more taxes, when Treasury mismanagement was common knowledge.

By 1789, the flow of money sputtered and then stopped.

Previously, during grave crises such as in 1769, the King had unilaterally slashed debts and forced creditors to accept a haircut. But now, the debt had grown larger and was no longer in the hands of a few financiers; it was in the hands of a whole class of bankers and speculators who were prepared to put up a fight and challenge the King’s authority.

Poor harvests were the tipping point

1788 was a bad year for farmers. Early summer heat waves, followed by July storms and hail, led to a poor harvest. In 1789, erratic weather and Necker's interventions led to increasing food prices. The prices of corn and bread peaked in July 1789.

Riots against the rich broke out, with protesters demanding fixed bread prices11.

“A labourer in Paris in 1789 would earn from twenty to thirty sous a day, a journeyman mason forty sous, a joiner or a locksmith fifty sous. If they were fathers of two children, these poor people would have to buy around eight pounds of bread a day. When the price of a four pound loaf of bread rose suddenly eight or nine sous to twelve, fifteen or even twenty sous, most wage-earners found themselves faced with imminent disaster. It is therefore not surprising that workers were more concerned about the scarcity or abundance of bread than about higher wages…12”

Necker was dismissed in July 1789, and soon after, the people stormed Bastille, starting the French Revolution.

There are layers and layers to this story and a newsletter isn’t enough to cover everything.

In this piece I wanted to focus more on the role bad money management played in starting the Revolution. But money was only one aspect, a big one but still one part of the whole picture.

A long-term consequence of the excesses of the 17th century, was a drop in France’s fertility rates in the mid-18th century. The research shows that the diminished influence of the Catholic Church, which led to the loosening of traditional religious moral constraints nearly 30 years before the French Revolution, was the key driver of this fertility decline. Eroding the population advantage France had over its rival England.

Read the fascinating research here→ Frances baby bust.

Filtered Kapi #62

Read more here→ Early French and German central bank charters and regulations by Ulrich Bindseil Pg 75-81

The shadow of John Law's Mississippi Bubble, which had burst five decades earlier, still loomed over France, making the nation wary of banks. Even the Caisse d'Escompte was cautious about appearing too bank-like. However, as France's financial needs grew, the Caisse's convenience for business transactions became increasingly valuable.

Modeled after the highly respected Bank of England, the Caisse d'Escompte seemed poised for success, despite the trauma inflicted by Law's scheme.

What I mean when I write,

Government- the decision makers running the country,

State- a ghostly presence who is threatening/oppressive/omnipresent version of the country,

Treasury- financing department of the Government.

Read more here→ “Was There a Solution to the Ancien Régime's Financial Dilemma?” by Eugene Nelson White

The radicalization of the French Revolution led to the closure of the bank in August 1793. However, the Banque de France, established in 1800, followed the Caisse's model and can be considered its reincarnation under a new name. From the paper mentioned in footnote 1.

Calonne took advantage of a significant influx of foreign money, particularly from the Netherlands. This shift of Dutch funds from London to Paris was partly due to the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. It's estimated that between 24% and 41% of investment in French loans came from foreign sources. From the paper mentioned in footnote 4.

Ibid

The original purpose behind levying the Taille was to finance wars. Therefore, it was charged only on the non-combatant population, meaning the commoners, for whom it served as a way of buying out of conscription.

This exemption was rooted in the social hierarchy of the time, where nobles were expected to provide military service (thus paying a "blood tax"), while clergy, who were not required to fight, were excused. Thus, for any new direct taxes such as capitation tax and vingtième, exemptions were sought on the pretext they were exempt from paying the Taille. From the book mentioned in footnote 9.

From the book mentioned in footnote 9.

Might be what is happening in many countries in the globe currently, India & UK included