How in 1947, the Indian State engaged in violence, and ostracised the Mewati Muslim Meo community

The years long attack, led by Sardar Patel under the guise of protecting Hindus and Sikhs questions the "secular" portrayal of India, even today

Hi there,

While on the hunt for interesting stories during the coming together of India in 1947, I discovered accounts of brutality faced by a section of Indian Muslims.

Writing this post deepened my understanding of the mahol, the atmosphere, during Partition which permitted and encouraged people to commit heinous crimes. I gained insight into the dread people felt, the thinking of Patel and Nehru, and the shortcomings of a budding “secular” India.

Beneath these atrocities, is the narrative of us v/s them, which paints one community as the villain. It is terrifying and sad that we fall for this storyline again and again. If we honestly acknowledged our history, we could learn to be more inclusive.

Most importantly the repercussions of the violence can be seen even today, 77 years after independence and the wounds are visible if we just look hard enough.

Let’s go,

Sowing hatred against Meo Muslims

In the months before Independence, India burned. Religious politics divided the people.

In the princely states of Bharatpur and Alwar, Muslims suffered the brunt of violence. Militant-minded workers of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Hindu Mahasabha aided these crimes.

The two states, located in present-day Rajasthan, lie a three-and-a-half-hour drive from the capital New Delhi. Atrocities occurred right under the noses of freedom movement leaders. The Rajas and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel's vicious treatment of Meo Muslims, using state forces against them, tells a chilling tale.

On 12th August, 1947, the Alwar army defeated a force of 10,000 Meos from Alwar, Bharatpur, and Gurgaon (now Gurugram). After pushing them into the hills, soldiers systematically hunted them down1.

Edward Wakefield, joint secretary of the Political Department, passing through the area, witnessed: “Charred corpses by the roadside, children with severed limbs, mutilated women with gaping wounds. I saw houses set alight, with armed men waiting outside to cut down anyone escaping the flames.”

Between May and August 1947, 30,000 Muslims were killed in Bharatpur and neighboring Alwar. Up to 20,000 were forced to convert to Hinduism and an estimated 100,000 fled to the relative safety of Gurgaon district.

Villages were razed to the ground and mosques desecrated by activists belonging to the RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha2. Meos retaliated by spoiling Hindu temples, prompting further reprisals. Many who fled never returned, settling in other Indian states or migrating to Pakistan.

Bharatpur's ruler Brijendra Singh and Alwar's ruler Tej Singh, both pious Hindus committed to Hindu nationalism, aided the massacre. They aligned closely with Hindu Mahasabha and RSS ideology, which deemed Muslims enemies and foreigners fit to be driven out. Land capture also played a role.

This planned, calculated massacre was carried out with thoroughness.

A call for revenge fueled the violence—revenge for Hindus killed while fleeing West Punjab (now in Pakistan) and in Noakhali, Bengal. Rumors of pro-Pakistan activities closer to home amplified fears that Hindus were targets, sowing seeds of division.

The Meos demands for sovereignty

In December 1946, the previous year, a meeting of Meos was held at the village of Teengaon in Bharatpur. They passed a resolution calling for a separate Meostan state, comprising Mewati-speaking Meo-majority areas of Punjab, Alwar, and Bharatpur. It might sound unbelievable today, but they demanded a sovereign Meostan stretching from Mehrauli in Delhi to Bandikui in Rajasthan's Dausa district3.

The Meos assumed that the whole of Punjab—then including Haryana and parts of Himachal Pradesh, as Jinnah demanded—would become part of Pakistan. Thus, Meostan would border Pakistan to the west and India to the east.

Propaganda in favor of Meostan ensued. At a panchayat meeting on February 3, 1947, in Alwar's Tijara area, organizers unveiled a new song, Tarana-e-Mewat (anthem of Mewat)4.

This movement threatened existing rulers' sovereignty, who had their own plans.

Bharatpur's ruler, Brijendra Singh, dreamed of a sovereign Jatistan, believing Jats from Bharatpur to Delhi and beyond would support him and his cousin, the Sikh ruler of Faridkot.

Meanwhile, Gurgaon’s Meo’s, aided by other Muslims began rioting, killing Hindus. Rioters entered Alwar and burnt down some villages. On April 3, armed Meos gathered near a hill in the Tijara area of Alwar. They had rifles, swords, axes, and other weapons. They fired upon state police that had come to disperse them5.

The two darbars cracked down on the Meos, triggering retaliation: Meo’s attacked a police patrol, looted a village, and razed another village. The Meos' history of defying authority, serving in the Indian army, and revolting against oppressors marked them as Enemy No. 1. Their strength in numbers and lack of representation in administration compounded the issue.

While these acts of lawlessness hardly justified Alwar council's claim of facing a rebellion, it provided Alwar and Bharatpur authorities the pretext they sought.

Adding fuel to the fire, was the problem of geography. Alwar and Bharatpur bordered the contested lands of eastern Punjab, and uncertainty about whether it would become part of Pakistan or India led communal forces to intensify hostilities.

In April 1947, Narayan Bhaskar Khare was appointed as Alwar’s Dewan (Prime Minister). He had also served as the deputy president of the Hindu Mahasabha, and he aimed his ire against India’s Muslim minority. In July he wrote, ‘No Musalman [sic] can be trusted to be faithful to Hindustan. In case of any big emergency, the Musalmans will surely act as saboteurs’6

Khare's agenda aimed to “restore Hindu Rashtra” after the transfer of power.

The two sides clashed on 12th August 1947, when the Alwar army crushed a force of 10,000 Meos.

Who are the Meos?

Majority of the Meos were farmers, skilled at cultivating the dry, arid land of their region. Historian Shail Mayaram estimates around 60% of the Muslim population in the Rajputana were Meos7.

Their customs blended Hinduism and Islam, creating a cultural identity distinct from Sunni or Shia Muslims.

It did not matter that this Mewati peasant community, had always worn its religion lightly, celebrating religious festivals with their Jat and Hindu neighbours. However, being a Muslim Meo in Bharatpur, Alwar, Gurgaon, or Delhi, now, meant being seen as a Muslim, anti-national, and likely Pakistani.

Many Meo leaders participated in the freedom struggle, including Chaudhary Yasin Khan, Chaudhary Abdul Haye, Sardar Mohammad Khan, and Syed Mutalabi Faridabadi. They opposed the idea of Meos migrating to Pakistan. In Haye’s assessment, “For a Meo, there was nothing to choose between a Pakistani Muslim and an Indian Hindu so far as communalism was concerned. All they had in common at most was their title of Muslim.8”

Support from the Central Government

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel's support for Khare, Dewan of Alwar deepened the divide. As Home Minister and head of the Ministry of States department, Patel played a crucial role in bringing the Rulers of Princely States into the new Dominion of India.

Khare convinced Patel that failure to suppress the Meo “revolt” would result in Meo-majority areas attempting to join Pakistan. Patel ordered the armed forces of both states to evict all Muslims from their areas9.

This action reinforced the perception of a Hindu-dominated Congress Government in New Delhi.

Lieutenant General Francis Tuker, commander of the 6th Jat Regiment, commented on Patel’s “complete lack of response to our repeated appeal for troops to be sent to the help of the unlucky Muslims being obliterated in the Hindu States of Alwar and Bharatpur”10.

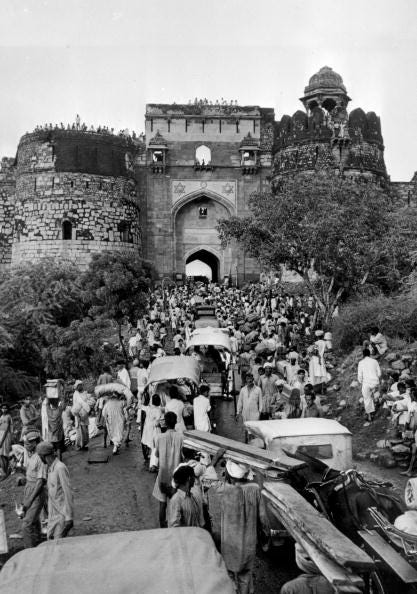

Unarmed Muslims fleeing with their belongings became targets.

As per an article on Scroll.in,

A former military assistant to the Alwar ruler, who [Historian] Mayaram interviewed in Alwar in 1993, admitted that “it had been decided to clear the state of Muslims. All the Meos from Firozpur Jhirka down, were to be cleared and sent to Pakistan, their lands taken away.” He went on to detail the “clearing up” and “cleaning up” operations (the officer called it “safaaya” or cleansing).

“Alwar was divided into four sectors under different army officers, to clear the state of Muslims.” he said.

In Tijara, a Muslim-concentrated tehsil, the Alwar army located itself on a hill, with the Meos down below in the valley. “We killed every man,” the military assistant told Mayaram. “All of them. The next four days we had to do the clearing up operation. My men and the villagers dug men’s graves, threw their bodies in.”

The culmination of the operation was the massacre at Kalapahar, north of Alwar. A second Alwar army veteran recounted to Mayaram, “Naugaowa was a large Meo stronghold. We butchered them. That was the last battle of Mewat.” The Meos had fled to Kalapahar to try to protect themselves.

“To finish them off”, the veteran noted, “we made a three-pronged attack from all sides, using the police and army. It took us more than two months, July and August during the rains to clear the whole bloody area.”

He added: “Not a single Muslim was left in Alawar. In Tej Singh Singh’s rule not a single mosque remained. Alwar was the first state to clear all the Muslims. Bharatpur followed”. According to the veteran, “the two rulers used to consult each other”

The account of the clearing and cleaning up operations was echoed by several military officers who Mayaram interviewed.

Killings were accompanied by forced conversions, and the abduction of women and girls. According to an officer Mayaram interviewed in Kaman, armed columns, on reaching Meo villages, would announce “either be killed or show a white flag and convert, become Hindus”. The Shuddhi Sangathans (literally, cleansing squads) of the Arya Samaj would shave the men’s heads, leaving a top knot and making them eat a piece of pork. They were made to recite the Hindu gayatri mantra and take an oath on sacred water drawn from the Ganga. “The Quran had to be put into the flames,” he said.

Before the massacres, the 1941 census showed that Muslims had made up 26% of the population in Alwar and 19% in Bharatpur 1941. After the killings, conversions and flight, the 1951 census showed that this dropped to 6% in both states11.

Ian Copland, an authority on the transfer of power, estimates that the toll in Partition-related violence was in the vicinity of 50,000 in Alwar and Bharatpur.

By autumn 1947, only 40,000 Meos remained in Alwar out of a population of 100,000-140,000, with almost all forced to convert to Hinduism to save their lives. Similarly, about 60,000 Meos had to leave Bharatpur. While some moved to Pakistan, the majority settled in nearby Gurgaon villages12.

Division within the Congress on handling the Meo “situation”

Nehru and Patel clashed over the handling of the crisis. Nehru was trying to make Muslims feel welcome in India, while his deputy was trying to deport them.

Aware that Kashmiris watched the government's actions, Nehru strove to build an inclusive country. However, Patel and his allies frequently thwarted his efforts.

Patel believed in the ideology that Muslims, having demanded Pakistan’s creation, had made their bed, and now they should lie in it. Added to this was the insult that the Meos had engaged in rebellion against the State, thus he perceived them to be enemies of a united India. However, since Congress policy forbade compulsory repatriation, the hard-liners tried to pressure the Meos into leaving voluntarily.

Refugees established camps wherever they found space and security, primarily in Old Delhi, but relief remained elusive.

In winter 1947, Patel defied the Congress Party line by ordering the Gurgaon commissioner to evacuate Meos from makeshift camps to Pakistan. Nehru, upon learning this, immediately countermanded the order and instructed the State Government to return all Meos from Alwar and Bharatpur to their original lands for rehabilitation. However, officials never received Nehru’s directive13.

Patel ultimately compromised, supporting a poorly implemented, staggered resettlement program.

When Khare was told that that Nehru wanted him to accept the Alwar Meos back, his reply was, “Once they enter the Alwar State they will be tried [sic] as rebels and shot.”

The forceful takeover of Meo villages

Fear of Muslims was the primary reason to push them out, but once they were out capturing their property became the priority. Greed fueled the bureaucracy’s decision making.

In Bharatpur, in a few months after the exodus of the Muslim population, the State decided to sell the “abandoned” land to local cultivators. They reasoned that leaving the land untouched would result in considerable loss of revenue to the State and fall in the sale of crops. So sure, were the bureaucrats that the Meos would not return that thousands of acres of land in Meo villages was sold14.

The Maharaja of Bharatpur expressed delight that no Muslim was left in the state.

Meos became yesterday's problem as the State shifted its focus to growing more food on the land left behind.

On December 19th, 1947, Mahatma Gandhi addressed a refugee camp in Ghasera village, 45 kilometres south-west of Gurgaon. Calling Meos the “backbone of India”, he urged them to stay, and promised them a dignified life, assuring them that harmony would soon be restored15.

Gandhi’s address was also heard by Meos who had migrated to Pakistan. Finding themselves lost in a new land, they heeded his advice and chose to come back.

Relocation but where?

In September 1948, after a year of displacement, the Meo “squatting problem” became big enough for the bureaucrats to look for a solution. They decided to settle the Meos in a compact area on the borders of the Gurgaon district and the newly formed Matsya Union. This area included cultivated land in Nuh and Ferozepur Jhirka tehsils of Gurgaon and adjacent land in Tijara and Pahari tehsils of the Matsya Union. The Matsya Union was formed in early 1948 by absorbing Alwar, Bharatpur, Dholpur, and Karauli.

At the heart of this bureaucratic paper plan, was that the Meos should not be given their original land, to avoid any communal flare up. The bureaucrats did not want to mix Meos with refugees and local Jats and Mahajans.

Sardar Patel, emphasizing the history of the Meo’s in the region, believed; “of Meos is not a Hindu-Muslim problem at all. It is virtually a problem of internal feuds between twos sects viz. Meos and Jats.”

Patel believed Meo’s who migrated to Pakistan forfeited their ancestral property, giving the government the right to use the land as they pleased.

Despite the threats to their life and against bureaucratic wishes, about 25,000 Meos returned to their original villages as sub-tenants or labourers. Locals preferred Meos as sub-tenants/labourers due to their skill in cultivating the dry lands.

Meos chose to work as sub-tenants or laborers in their original villages rather than take the reserved lands in Gurgaon.

Nehru, seeing the peaceful acceptance of Meos, hoped the remaining landless Meos would soon resettle “peacefully” and “naturally.”

The Ministry of States (MoS) headed by Patel, continued to push its agenda, claiming Meos had been “residing” in Gurgaon for over two years and “infiltrating” Alwar and Bharatpur. This had made refugees “anxious” and Meos “apprehensive”. They argued Meos should move to the compact area, as per bureaucratic wishes, “in the interest of their own security.”

In 1949, the position of the Meos was that in Alwar, 95% Meos were in their original homes and 50% on their original holdings; in Bharatpur, 50% were in their old villages and 50% in a “fluid state”. It was no longer possible “to insist on Meos to occupy the compact area without uprooting them [again] from their homes.”

The officials admitted that “local population or a large percentage of it welcomed the return of the Meos”. However, this statistic fails to show how many Meos were relegated from landowners to laborers or tenants on their own land.

Patel, having his plan thwarted, was not happy with the situation and lashed out at the officials in the Rajasthan Government (successor government to Matsya Union) believing them to have encouraged “the influx of these Meos.” Next, he wanted them “to prevent further influx of Meos” they were also to be “careful and vigilant about the Meos from Pakistan.” The MoS maintained that the remaining displaced Meos should not receive their original lands but be allotted areas according to the compact plan, segregating them. They proposed allocating former Meo land to other refugees for internal security16.

Patel wanted to close the “Meo chapter” and focus on mechanical cultivation schemes to “grow more food” and refugee resettlement schemes.

In February 1950, there remained 1,13,885 Meos in neighboring Gurgaon; close enough to their former homes but not in it17.

The aftermath for the perpetrators

On 7th February 1948, Patel succumbed to pressure. He dismissed Khare, Alwar's Dewan, and placed him under house arrest.

The rulers were removed from their gaddi, seats, and the administration of Alwar and Bharatpur suspended, not due to their participation in the massacre of Muslims, but due to their ties to the Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS. These organizations were believed to have played a role in Mahatma Gandhi's assassination on January 30, 1948.

The Rajas had already acceded to the Indian Union, and in March 1948, about nine months after the peak of violence, Alwar, Bharatpur, Dholpur, and Karauli were merged to form the Matsya Union.

Years later, V.P. Menon, Patel's right-hand man and key figure in persuading the rulers of the Princely States to join India, admitted, “I took Alwar and Bharatpur without their consent. There was a mad killing spree on there. The Diwan of Alwar [Khare] was encouraging mosques and graveyards to be demolished.18”

In an independent India, the perpetrators walked scot-free.

Khare later became President of the Hindu Mahasabha and was elected to Parliament in 1952.

An investigation into Khare's and Bharatpur rulers' involvement in the Meo massacre resulted in no punishments. Adding insult to injury, the former ruling families and their successors reinvented themselves as politicians and contested parliamentary elections.

Like other princely states, the former rulers retained their royal titles and received a privy purse. These privileges continued till 1971.

Memories of violence and Questions left unanswered

Sardar Sajjan Singh, a member of legislative assembly from East Punjab, from his time visiting twelve villages of Alwar and Bharatpur districts, observed most Muslims were depressed, demoralised and dejected.

“In the city of Alwar, all mosques have been demolished...On the vacant side of Lal Shahi Masjid, a new building has been erected...The site of Jama Masjid has been occupied and shops have been erected thereon. On the vacant side of another Masjid, a new building [is] being constructed...Meo boarding house and Sarai are being occupied by refugees…at Lakshmangarh town, debris of a mosque has been auctioned by the government.”, wrote Singh to Nehru.

[…]

He followed his claim with an illustration. In Govindgarh town of Alwar district, Chaudhary Nathoo, who was the owner of 550 bighas of land, had been restored 140 bighas, including 70 bighas belonging to some other Muslim. Then, more callously, in Lakshmangarh, which had the most fertile lands in the region, “neither the refugees [had] been allotted any lands nor the Meos [had] been given back their land in full, [with] lands [being] leased to local 31 Hindus on nominal rents.”

Shyam Lal, the Deputy Director, Relief & Rehabilitation Rajasthan, admitted to Singh on July 19, 1950 at Alwar that those Meos who had been restored their property “do not enjoy proprietary rights and no decision has been taken by the Rajasthan government in this respect.” Singh then gave an instance of “alternate allotment.” In village Dhakadinapur, tehsil Deeg, district Bharatpur, 55 families of Meos were living before Partition. During the disturbance of 1947, 5 families left for Pakistan. The remaining 50 were entitled to 12.61 bighas of land in their own village, but had been resettled in 5 different, adjacent villages. His next series of queries juxtaposed prejudice next to bureaucratic claims of parity, practicality and preference:

In Rajasthan, constitution is being violated to please the goddess of communalism…under what provision of law, the ‘compact area, reserved villages and alternate holdings’ proposals have been put up? There is no justification…to order the Meos to be resettled without disturbing the refugees…The refugees should be put into possession of evacuee property only. There is no reason why the Meos and other Muslims of Rajasthan be victimised for the rehabilitation of the refugees. Government has no right to rehabilitate the refugees at the cost of Rajasthan Muslims.19”

The questions raised still haunt us today.

My takeaways

Unpacking our past is always complicated, especially when dealing with communally sensitive stories.

In school, history is taught from a one-sided perspective. But what does independence or freedom mean to people leaving their homes, ancestral lands, and sometimes family members behind for an unknown land?

The perception of freedom changes depending on one's location, identity, and financial status. Are you listening to Nehru's 14th August, “Tryst with Destiny” speech from the safety of your home or starving in a refugee camp?

This story shows an Independent India where the State had an authoritative bent, pushing its agenda with unchecked power.

It is horrifying to see a strong man abusing the government's machinery against a particular community. This narrative repeats throughout our history: the majority feels threatened by a minority, and during times of fear, we become more susceptible to violence, raising arms and revealing our dark side.

Patel failed here. This doesn't match the persona we've constructed, but he remains a hero to many and a villain to some. He failed to grasp Gandhi's vision of a secular, democratic India.

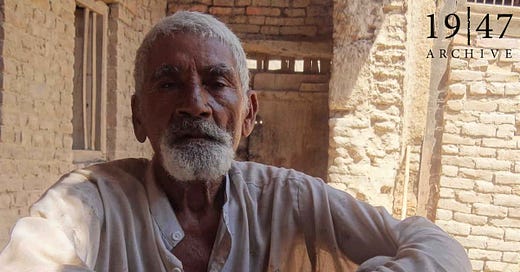

Additional Cool Stories: The 1947 Partition Archive is a collection of oral histories of Partition witnesses and survivors. I found stories of people who were forced to flee Bharatpur and Alwar (see the first image- it is of Mr Rehmat Ali, one such refugee), it made history come alive for me! By reading their stories we can try and understand what they went through.

P.S. Hey, thank you for making it till here! 👧🏽🙌(this is me high fiveing you). All the articles on Filtered Kapi take a lot of time, love and care to write. I would love it if you could leave a comment so that I know you exist, and I don’t feel like I am a weirdo talking into the ether!

P.P.S. I will be in Bombay from March 14th to 16th and in Jaipur on March 17th and 18th. If you're around, I'd love to meet up for coffee!☕

Filtered Kapi #68

From the book Dethroned: The Downfall of India's Princely States by John Zubrzycki Chapter 7 Endgames of Empire. Same reference goes for the statements made by Edward Wakefield and Francis Tuker.

See point no.1

See point above

See point no.3

See point no.1

From an article on Frontline→ A tale of two broken promises, and the rise of Muslim ghettos in India. Also, if you want to know more about the Meos and their experience the book to read is Resisting Regimes: Myth, Memory and the Shaping of a Muslim Identity by Shail Mayaram. I have not read it yet but every paper I have read quotes her work.

See point above

See point no.1

See point no.1

From an article on Scroll→ In the shadow of Partition, state-sanctioned atrocities aimed to wipe out Meo Muslims in Mewat

Bureaucracy, Community, and Land: The Resettlement of Meos in Mewat, 1949–50 by Rakesh Ankit Page no. 4

See book mentioned in point no.1

See paper mentioned in point no. 13 Page 22

See point no.6

See paper mentioned in point no. 13

See paper mentioned in point no. 13 Page 26

See point no. 1

See paper mentioned in point no. 13 Page 29, 30 & 31

Aditi, thank you for this eye opening, informative piece. So well researched.

How little we know of our history! And indeed how complicated it is! Thank you Aditi for researching and bringing up such nuggets from the past!