Bombay's first female doctors and the men who made it possible

How it led to the construction of India's first hospital to be run by women

In 1883, Dr. Edith Pechey had to weigh two options in front of her.

She could either continue practicing surgery in Vienna or take charge of a yet-to-be-built hospital thousands of kilometers away in Bombay (now Mumbai), considered the backwaters of her profession.

Dr. Pechey chose to take the position in Bombay. A few years later, she became the Senior Medical Officer at the Cama Hospital, one of the world's first medical facilities staffed entirely by women.

Over the next twenty years, her actions changed Indian’s perception of female doctors and cemented the benefits of a hospital in the minds of locals.

This was possible due to the actions of a few men who led the charge in making this a reality.

It’s a fascinating story so let’s dive in.

A society that ignored the medical needs of women

In 19th-century India, women were kept busy with household duties and childcare. Society felt that working outside the home would be both mentally and physically challenging for women.

These societal norms were compounded by practices that further restricted women's mobility. For example, some high-caste women confined themselves to the zenana, private quarters in their homes where unrelated men were not allowed to enter. They also practised purdah, avoiding public spaces and, when appearing in public, covering themselves from head to toe to shield themselves from the male gaze. These customs created significant hurdles for male doctors attempting to examine or discuss medical issues with women.

This left them isolated and dependent on the whims of the male members of the family.

Because women were relegated to the background of society, public health infrastructure was not set up to serve them.

Even in 1882, there was no Indian female having earned a medical degree in the Bombay Presidency. This was twenty-five years after the Crown had taken over from the East India Company. In Bengal and the North-West there were one or two women doctors connected with Christian missionary societies. There were no qualified women doctors to be found elsewhere in India.

It was three years later, in 1886, in Calcutta (now Kolkata), that Kadambini Ganguly became the first Indian woman to practice medicine as a doctor.

Access to modern healthcare was limited, compounded by scepticism towards western medicine. Women looked towards traditional herbal medicines to cure their problems. If a problem persisted, it was often perceived as ‘the toll of Nature’ or ‘the will of God.’ The concept of hygienic birthing conditions or postpartum care did not exist. Women gave birth at home under the care of midwives trained in religious and traditional practices.

Thus, the problems of half the population were unacknowledged or worse deemed unimportant to cure.

This was the context under which Dr. Pechey came to India.

Her appointment was partly due to an American businessman, Mr. George Alvah Kittredge. Appalled at the lack of medical care for women, Kittredge, along with other businessmen in the city, raised funds to develop health infrastructure catering to the needs of Indian women.

The reality in Kittredge’s words1,

I remember very well when laying this scheme before one of my native friends in 1882 being told by him that he had just lost a favourite daughter through his inability to obtain for her female medical assistance. He urged her to receive the advice of a doctor of the other sex, but she refused, begging her father to let her die rather than subject her to treatment by any male doctor ; and the poor girl died, though her case was not a serious one under skilful treatment. At that time, however, her father's money, which he was ready to spend for her, was of no avail, as there was not a lady doctor in the Presidency.

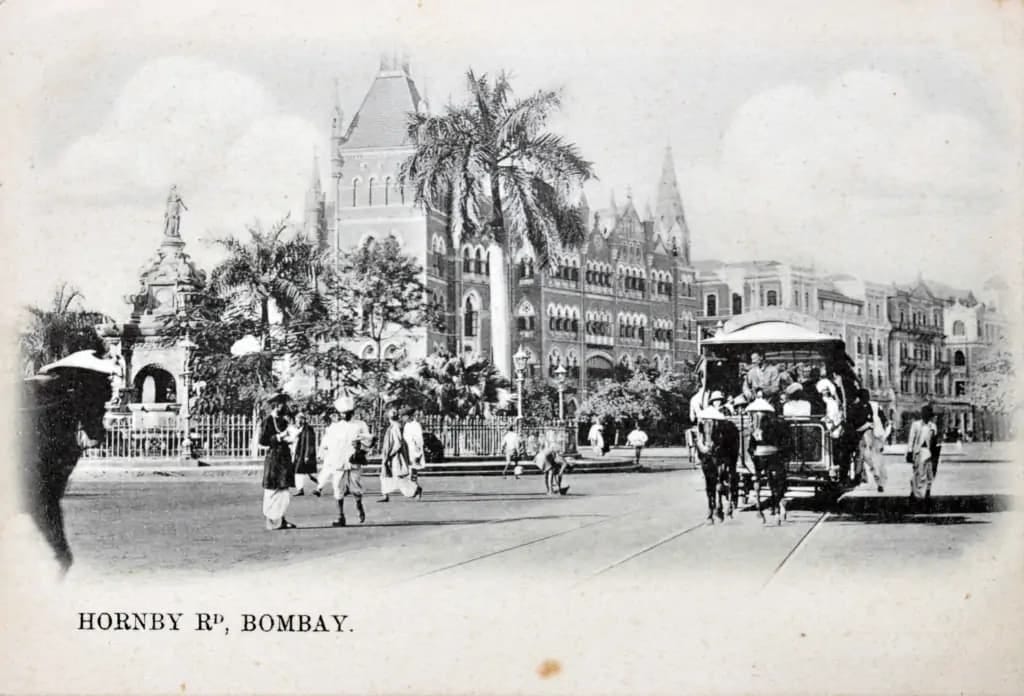

The entrepreneurial Kittredge, who worked in the city for forty years and established the first tramways on the streets of Bombay, knew the movers and shakers of the city.

Setting up the Fund

To combat the shortage of female doctors, the Madras and Bengal Presidencies had opted for a solution where women were trained in select subjects for a shorter duration compared to male doctors. This placed them in a better position than midwives, but they were perceived as inferior to their male counterparts.

Kittredge did not like this solution and with the money raised wished to “bring thoroughly competent and experienced ladies from Europe and America, those whose abilities, education and experience would enable them to take their places by the side of the other medical officers in this country.2”

In 1882, within three months of establishing the “Medical Women for India” Fund of Bombay, a princely sum of Rs. 40,238 was raised.

The Fund was unique, as it was not sponsored by the government but run and brought to life by private individuals desperate for a solution. Additionally, they did not discriminate based on community, caste or religion. Most philanthropy at the time targeted specific sections of the public.

Kittredge donated Rs. 2503 to the initial corpus of the fund, and an additional Rs.100 in 18854. Helping Kittredge raise funds, was the eminent social reformer, Sorabjee Bengallee.

Bengallee was a writer, activist, and philanthropist. His reputation as a man of integrity dispelled any doubts about the intention of the scheme. He donated Rs. 5005 to the initial corpus, and an additional Rs. 25 in 1885.

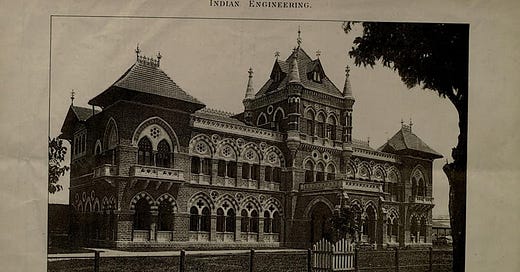

Setting up the Cama Hospital

Through Bengallee’s connections and efforts, on 1st March 1883, Mr. Pestonji Hormusji Cama, a Poona-based Parsi millionaire, agreed to donate Rs. 100,000, for a hospital for women and children, on the condition the hospital be named after him. Until then Kittredge and Bengallee had limited dreams, hoping to raise enough funds to open a dispensary.

Following discussions with the Government, it was decided the authorities would provide the site and cover maintenance expenses for the proposed hospital. Mr. Cama's donation would fund its construction.

Once news spread that funds were available for a women's hospital, officers of the Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy Hospital tried to secure the money for their institution. Their hospital was one of the few available for women, and it faced a perennial shortage of beds, with patients thronging every available space. The officials wanted the new building to be built near the existing hospital buildings, bringing it under their control.

Bengallee and Kittredge opposed this idea, as they wanted the new hospital to be separate and under the exclusive charge of women. Sorabjee fought tooth and nail, and emerged victorious. The site for the new Cama Hospital was fixed on 19,000 square yards of land on the Esplanade.

Extending beyond the walls of the central Fort Area of Bombay, it had large open spaces available making it an ideal location.

Who should oversee the hospital?

Both Kittredge and Bengallee were of the firm opinion that women should be in charge of the hospital. They wanted to empower women and believed this would open doors for female medical graduates to gain on-the-ground training.

This novel idea rankled the Government.

The administration, in cahoots with the Principal of Grant Medical College - the most prestigious medical institution in the country - stated their willingness to utilize the services “of competent medical women acting under the instruction and guidance of the male superior staffs.” Kittredge and Sorabjee understood they needed experienced women doctors to keep the critics at bay.

It was also decided the Fund would pay the fees for a handful of female medical students studying at the Grant Medical College.

Kittredge traveled to the U.K. to secure the services of suitable women to fulfill the Government's condition.

His efforts led him to Dr Pechey.

Simultaneously, Bombay University and Grant Medical College were asked to confer on women the same medical degrees given to men, upon the same conditions being met. The request was granted, opening doors for women to earn University medical degrees and placing them on an equal footing with their male peers. The Universities of Bengal and Madras soon followed, offering women the same degrees as men.

The hospital took roughly three years to be constructed, meanwhile the Fund-raised money to open a temporary hospital for patients at Khetwadi. In the mean time, a temporary dispensary was opened near Crawford Market.

As per Dr. Pechey’s Medical Report in 18856,

During the year there have been 5,998 new patients at the Dispensary, with a total attendance of 27,429. The numbers would have been much larger but for two reasons (1) the insufficiency of funds to meet the expense of drugs for a larger number, and (2) the want of more medical officers. The general public is apt to forget the amount of time required to see such a number as 100 patients daily. Even allowing only three minutes to each it takes five hours to see 100 patients ; and private patients would think themselves very insufficiently attended to were they dismissed with the amount of investigation which can be carried on within the limits of three minutes. More medical officers are urgently required, as frequently more than a half the fresh patients have to be sent away.

Furthermore, Mr. Cummoo Sulliman donated Rs. 20,000 towards a dispensary, the Jaffer Suleman Dispensary, named in honor of his late brother. This dispensary still stands today, connected to Cama Hospital.

The cost of the hospital building exceeded the initial estimate of Rs. 1 lakh. When the Government refused to cover the excess, Mr. Cama stepped in, contributing approximately Rs. 64,311. This brought the total cost to Rs. 1,64,311.

In August 1886, services at the Cama Hospital began with Dr. Pechey at the helm. The main building contained accommodation for fifty-two beds. On each side, there were two detached pavilions for special cases, each accommodating four beds. Additionally, there was a separate ward for fever cases, which also accommodated four beds.

Equal pay for services of equal quality

Dr. Pechey, ever the quick doer, learned Hindustani (similar to Hindi) to communicate with her patients.

However, there was a division of opinion in the managing committee of the Fund regarding how much Dr. Pechey should charge for her services, or if she should charge at all.

Dr. Pechey charged for professional visits the same fees as were asked by male physicians of the best standing, ~Rs.10 a visit.

Some committee members, wished that Dr. Pechey would visit the middle classes for a lower fee, citing middle-class patients’ inability to afford her fees. They strongly urged Dr. Pechey to attend to them at the dispensary for a fee of Rs.2 per visit.

Dr. Pechey, however, stood firm in her position, arguing that accepting a lower fee than the standard rate would imply she was inferior to her male peers.

She was willing to give her services for free by visiting the homes of sick individuals whenever any Committee member sent her a note requesting it. The Committee was forced to accept her position, with the unfortunate result that Mr. Sorabjee Bengallee ceased to take an active part in the work of the Fund7.

She won for herself and her staff the same salary as was paid to men doctors in similar positions. She believed that paying women physicians less would undermine their professional status and reinforce the misconception that women were less qualified than men8.

About Edith Pechey-Phipson

Dr. Edith Pechey-Phipson was nothing less than a force of nature.

She had impressed Mr. Kittredge, who praised her talents, education, and experience. An articulate and powerful public speaker, she became a driving force for cultural change.

To offer a glimpse into the depth of her knowledge, below are her words, written in December 1885, describing the causes of women’s suffering9.

It is interesting to observe how certain diseases obtain amongst certain races as the result of their special customs. The prevalence amongst Hindoo women of ricketts and scrofula is no doubt due to their custom of early marriage; the demands of maternity being made upon a system in which the bones and other tissues are not yet fully developed, the offspring is insufficiently nourished, and that at the expense of the mother. The purdah system prevalent amongst the Mussulman women tells most injuriously, especially in a closely crowded city like Bombay, and it is quite sad to see girls, who as long as they are allowed to run about and get fresh air are robust and healthy, fall victims, as soon as they are secluded, to consumption, the disease which always dogs the life of those whose time is spent in close ill-ventilated rooms. Mussulmans have repeatedly said to me, " All our women die of consumption." The Parsees, again, are specially liable to internal inflammatory maladies, the result almost invariably of the customs prevalent amongst them with regard to lying-in women who, being secluded for a lengthened period to the most unhealthy and dampest part of the house at a time when fresh air and protection from chill are most essential, often suffer life-long mischief in consequence. Many of the ground-floors in the Fort and Dhobi Talao are never free from the contamination of sewer gas, and it is really surprising that the women do not suffer more frequently from fever, diphtheria, and other drain maladies.

A great mortality is caused amongst children in Bombay by the custom, so common with some of the lower orders, of giving opium, and it is greatly to be desired that some check could be put upon this most murderous habit.

She was an independent thinker, used to questioning society’s norms.

As a member of the Edinburgh Seven, the first seven female undergraduate medical students at any British university, she fought to be admitted to the University of Edinburgh as a medical student.

As a first-year student, she qualified for a chemistry prize of £200, but it was denied to her because of her gender! Instead, it was given to a male second-year student who came in second.

However, the university ousted them in 1874, claiming it had ‘exceeded its authority’ in admitting them in the first place and thus had no further responsibility toward them. Not one to give up easily, she went to the University of Bern, passed her medical exams, and was awarded an MD. She became a licensed doctor by sitting for and passing exams in Dublin in May 1877.

She held the post of Senior Medical Officer at the Cama Hospital from its completion in 1886 until 1894 when she retired to continue in private practice. She was the driving force behind establishing a nurses' training school connected to the Cama Hospital, persisting until it was established. A tireless advocate for female education, she was also a staunch supporter of the few existing girls schools. She campaigned for wider social reform and against child marriage.

She was a pillar of support for Rukhmabai, the eleven-year-old child bride who rebelled against Hindu custom. She supported her during the grueling years of legal court battles and made it possible for her to attend the London School of Medicine for Women10.

She often gave lectures on education and training for women and was involved with the Alexandra Native Girls' Educational Institution.

In 1896, when bubonic plague broke out in Bombay, followed by a cholera epidemic raging throughout India for the next four years, she immediately offered her services.

She devoted twenty-two years of her life to service in Bombay, changing the city for the better.

The Fund achieved its objectives

By 1887, the Fund had fulfilled its promises of bringing competent women doctors, opening a dispensary for the poor, and establishing a hospital for women and children. Consequently, it placed the services of Dr. Pechey and Dr. Charlotte Ellaby, the Junior Officer, under government oversight - signaling the close of the Fund.

The success of the scheme was evident in the rising number of women pursuing medical degrees and the increased access to Western medicine for both rich and poor.

It's vital to note that this would not have been possible without the efforts of George Kittredge and Sorabjee Bengallee. They left their marks on the city, and we should know their stories. I've explored them below. If you look closely, you can see the city taking shape before your eyes.

Kittredge and B.E.S.T- the red bus plying on Mumbai streets today

In the early 1870’s, the people of Bombay needed faster public transport. Their options were limited to bullock carts, horse carriages and palanquins for hire. Many ideas were floated but failed to take off.

In March 1873, Kittredge and his partner Stearns won the right to construct, maintain and operate tramways on the streets of Bombay. To raise the funds for the project, Kittredge and Stearns floated a company in New York called the Bombay Tramway Company Limited and registered it in Bombay.

Construction began; steel rails were laid, and tracks and junction points made of cast iron with manganese steel tongue rails for extra protection were built. The ties linking the steel rails were made of Indian teakwood. The cost of the tramway tracks was ~Rs 24,000 per mile.

The service started on May 9, 1874, with trams drawn by one horse, and on broader roads, trams drawn by two horses. The tram service was a success; within a week, 3,135 passengers travelled on 294 trips. The trams plied two routes: Colaba to Pydhoni via Crawford Market, and Bori Bunder to Pydhoni via Kalbadevi, with a fleet of 20 tram cars and 200 horses. The service was praised for its speed, comfort, and convenience.

The fare from Colaba to Pydhoni was initially three annas. It was brought down to two annas within months, and by 1899, it had dropped to one anna.

In 1899, the company applied to run its tramcars on electricity. However, the Municipality decided to exercise its right to purchase the company. In 1905, a newly formed entity, the Bombay Electric Supply & Tramways Company Limited (B.E.S. & T Co. Ltd.), came into existence.

During its 31 years, the company had expanded operations, at the time of closing it had 1,360 horses in service. On the last day, 1st August 1905, the number of passengers zoomed to 71,947, and the takings amounted to Rs. 4,26011.

On May 7th,1907 the first electric tramcar plied on Bombay streets. Motor buses were introduced in July 1926. Red double-deck buses, modelled on London’s red public transport busses, came in 1937.

By Independence, however, the tramway had become an outdated mode of transport. In the decades after freedom, various loss-making routes were shut down and replaced with buses. The last Bombay tram signalling the end of an era, plied from Bori Bunder to Dadar on March 31, 196412, after 90 years of service to the people.

Bengallee and his contribution, which can be felt 125 years after his death

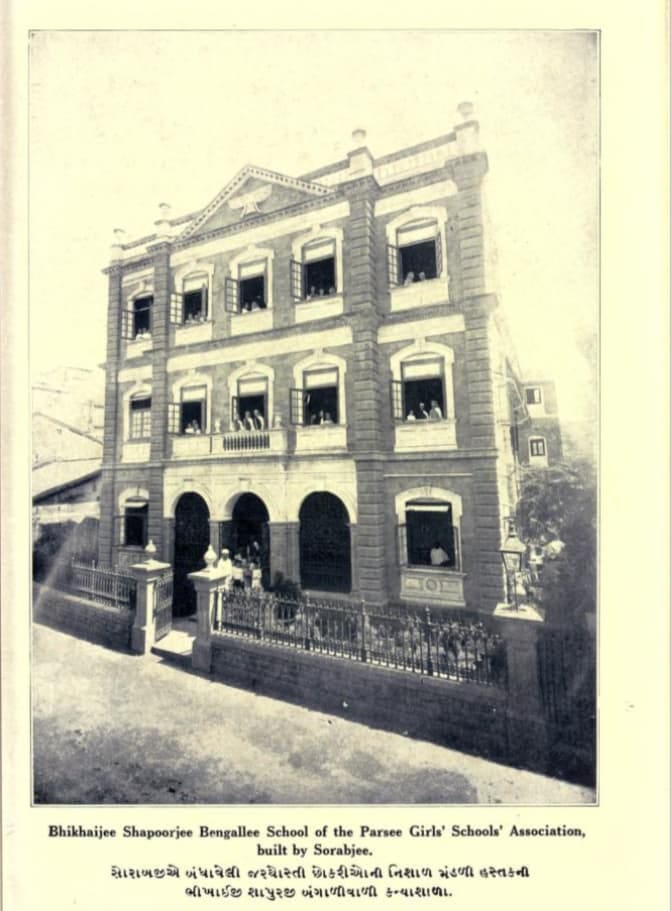

Bengallee funded the Bai Bhikaijee Shapoorjee Bengallee girls’ school, named after his mother, which today stands near Churchgate, South Mumbai.

He was actively involved in educational initiatives, serving on the management committees of various boards and trusts. Additionally, he funded several girls’ schools across India. He was unique because he did not narrow his focus only to his community, but aided initiatives shown by others and coaxed funds, when necessary, from the Government.

Bengallee briefly edited Rast Goftar, an Anglo-Gujrati paper. In the paper, social questions were discussed along with political and financial affairs bringing important debates to the fore.

Under Sorabji's guidance, the Rast Goftar warned against investing in reckless scripts issued by newly formed banks, shipping corporations, financial associations, and reclamation schemes. This was during the wealth explosion of the American Civil War (1861-1865), when Indian cotton was in high demand and traders, merchants, and bankers all profited from its booming price. Fearful of losing out, Bombaikers rich and poor, ploughed their savings into fanciful ideas, and the bust triggered by the end of the Civil War decimated their investments13.

He was a staunch supporter of Dr. Sir Temulji Nariman, obstetrician and dean of Grant Medical College, and helped launch the Parsi Lying-in Hospital (PLIH). Pregnant Parsee women were suffering due to being confined in dark and unventilated rooms; to combat such unhealthy customs, PLIH became one of the first maternity hospitals in the city.

In 1865, citizens of the city had to combat diseases like cholera and smallpox; water supply was infrequent, and the state of the markets and slaughterhouses left much to be desired. As a Justice of Peace (a position of power), Bengallee was critical of the heavy-handed actions of Municipal Commissioner Mr. Arthur Crawford and found discrepancies in the Municipal finances.

Bengallee's knowledge of finances helped bring the issue to the public domain. He, along with Sir Dinsha Wacha and other leaders, contributed to reforms enacted under the Municipal Act of 1872.

In April 1878, as a Member of the Bombay Legislative Council, Bengallee advocated for better working hours for cotton mill workers. Even though mill owners, The Bombay Chamber of Commerce, and even women mill workers were against any reform, through his advocacy, working hours were curtailed for men, women, and child laborers.

He was awarded the Companion of the Indian Empire (C.I.E.) by the colonial authorities.

Sorabji Bengallee was a man of many talents and triumphs and the above list of his achivements simply scratches the surface. He was a man of conviction and high morals, he went beyond caste, sex, wealth and helped people where he could.

Clearly, the people of Bombay felt similarly, and on his death in April 1893, a huge sum of Rs. 51,215 was raised to perpetuate his memory.

It was decided to erect a marble statue costing Rs. 22,000, located on the Oval Maidan. Rs. 25,000 was donated for the purpose of providing a building for the Municipal Churney Road Girls' school to be named after him. And the balance towards the maintenance of the building of the Bhikaijee Bengallee Girls' School14.

Closing thoughts

Today, for me Bombay is chaotic and exhausting. I don’t live there anymore but I still call it home. This story gives me hope that people can come together to change their circumstances. The hurdles Kittredge and Bengallee faced were daunting, but they weren’t alone, they pinpointed the problem and asked people for their money. And surprisingly, people parted with their money!

One thing I keep realising again and again is, we shouldn’t take things for granted. Just because you see them now doesn’t mean they were always there. Someone worked very hard for what we consider basic today.

You know what would make this story perfect? If there was a woman in the managing committee of the fund, or if a woman had Bengallee’s resolve to push the idea forward or if many women had donated to the fund (only a couple of them did amounting to 5% of the initial corpus-see footnote 5), but none of this happened. Women needed help from the opposite sex, this is a common theme of the time, and it makes me sad. I am glad to see that we have made progress since then though.

P.S. Hey, thank you for making it till here! All the articles on Filtered Kapi take a lot of time, love and care to write. Tell me what you liked, enjoyed, disagree with by leaving a comment so that I know you exist, and I don’t feel like I am a weirdo talking into the void!

Filtered Kapi #69

From the book A short history of the “Medical Women for India” Fund of Bombay, List of Donors Page 18→ Read here

From the book A short history of the “Medical Women for India” Fund of Bombay, Medical Report, 1885→ Read here

See point number 6

Read more about the trams here→ Different Tracks

To know more about the share mania, read→ How cotton caused India's first stock market bubble by me!

An amazing read ✨

This was so well researched Aditi and had so many fascinating stories about healthcare in colonial India.