Finance during the Mughal era

How the Rajas kept their treasuries full, and how that affected the common folk

Hi there,

Follow the scent of money and it will lead you to the best stories. I learned this in the first year of my writing journey.

Today I am sharing with you a handful of stories which show a slice of life during the Mughal era. Central to the story are the native moneylenders, the supporting cast is the Rajas and the common folk, the script writer is the East India Company.

For me they shed a light on the past in a way our history textbooks didn’t. I hope they find a place in your heart.

I found these stories while researching my last article, some of these I posted on Substack Notes, but they have been expanded and woven together for this piece.

Let’s go,

Benefits of the native banking system - Hundi

Before banks facilitated money transfers, the Indian subcontinent relied on the Hundi system - a network run on trust, enabling safe movement of money across vast distances.

In seventeenth-century Amber, India, this system was essential for tax collectors, revenue assessors, moneylenders, exchange traders, and army suppliers - all of whom played a vital role in keeping the state treasury full.

The state relied heavily on the moneyed class, so much so that appointments in the revenue department were made from families belonging to the banking class. Amber - and later Jaipur - became known as being under "bania raj", that is, run by the merchant and banker communities (banias).

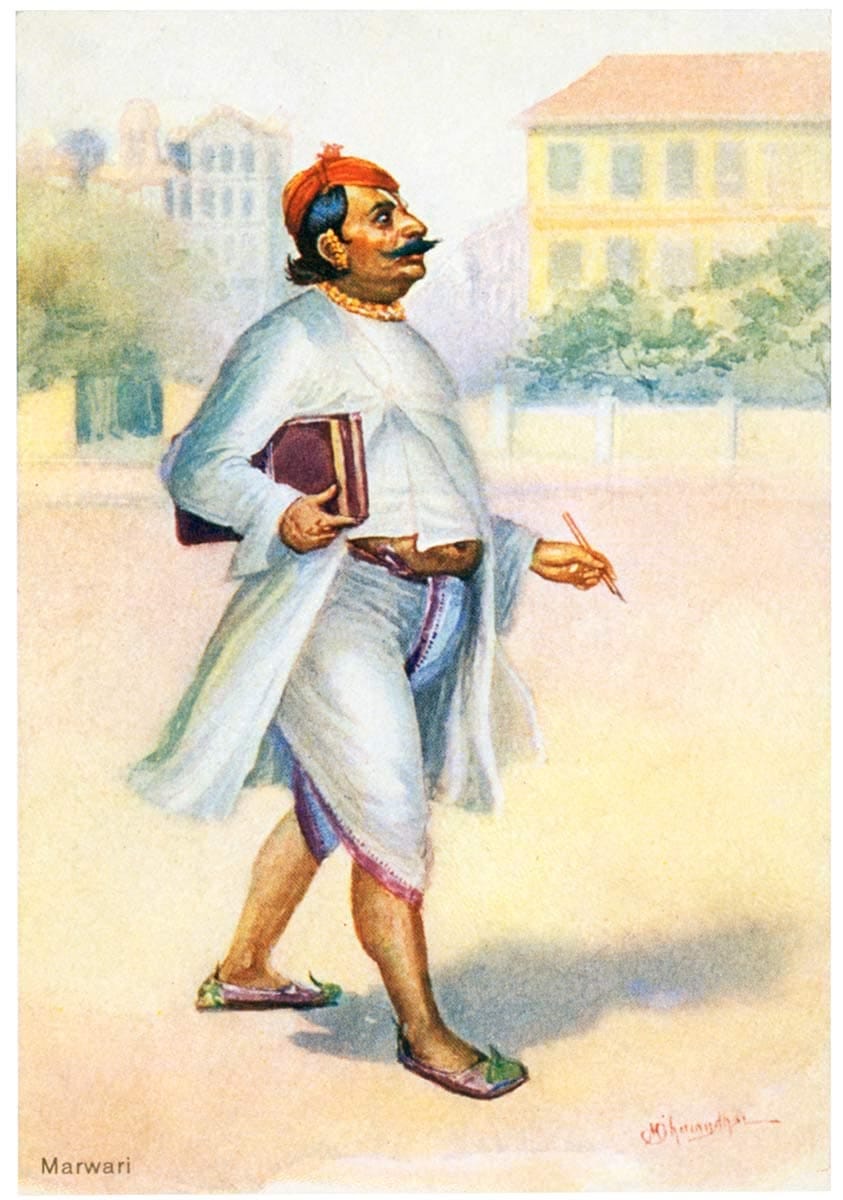

People were able to accumulate wealth when Rajput rulers depended on them to supply food to their armies and ensure that soldiers fighting in far off regions received their pay. These suppliers to the army called Modi and Poddars also engaged in local trade and money lending. Belonging to the Vaishya class, they came from the Marwar region of Rajasthan and hence were called Marwaris by the locals.

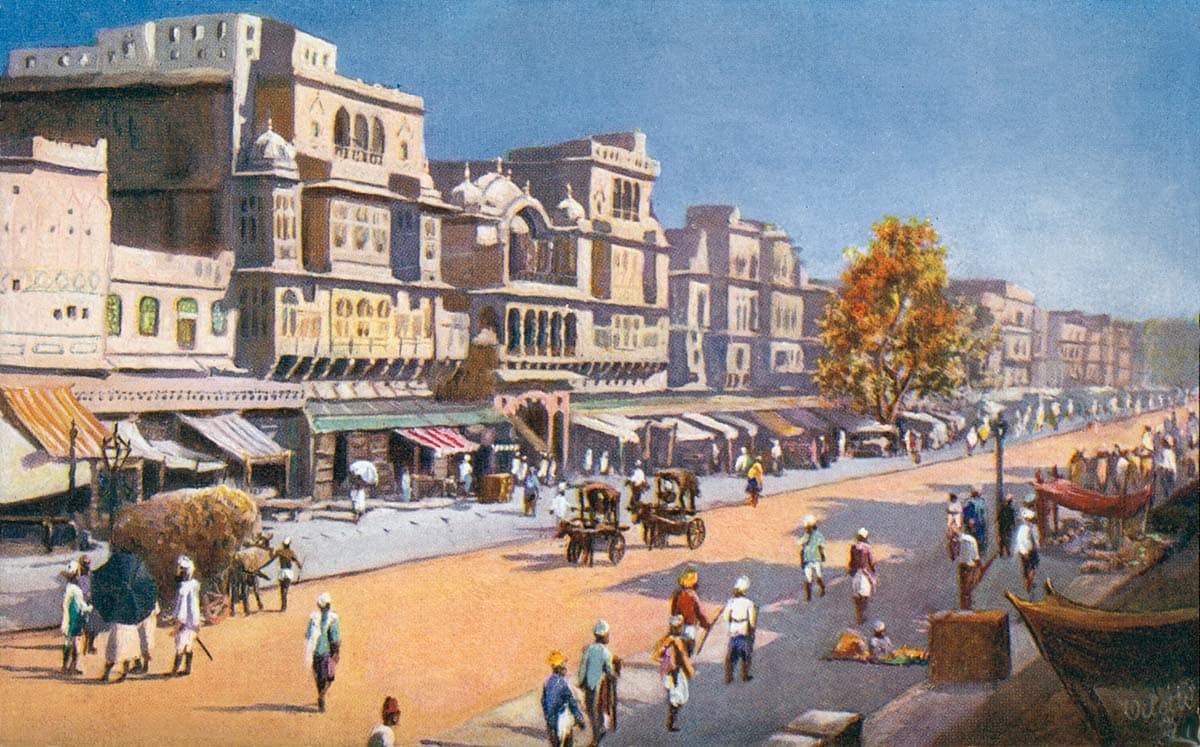

Under royal patronage, the pre-dominantly Marwari bankers and traders established their presence, connecting Rajputana in the west with Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in the east.

As they expanded, bankers faced numerous challenges, such as receiving money in one currency and remitting it in another. At the time, dozens of currencies competed with one another for dominance. These bankers played a vital role in price discovery of coins by monitoring circulation, the quantity being minted by rulers, purity of the coins, and demand for coins relative to one another.

The hundi was a sort of promissory note, and the system relied on trust and reputation. It served as the lubricating oil for the sub-continent-wide banking system.

If a merchant in one city wanted to send money to another, he would first approach a trusted banker or moneylender and deposit the funds. The banker would then issue a hundi, which the merchant could send to his business partner or family in the destination city. The recipient would present the hundi to the related party of the banker/moneylender in their city, who would pay out the amount specified in the hundi. Later, the two bankers would settle the accounts between themselves.

Moneylenders used hundis to facilitate trade by giving credit and easing remittances, even in remote villages. They played a vital role in bringing rural goods to urban localities and vice versa. With agents of bankers holding and remitting money as indicated by the hundis. The seller of goods could easily sell to a buyer located in another town willing to pay in another currency.

Without this trust-based system, trade across the Indian subcontinent would have been far more cumbersome.

Using Hundis to raise funds for the State Treasury

Moneylenders played an important part in the collection of taxes.

Land taxes made up the largest portion of state revenue. The process of converting land revenue into cash required a middleman to be present.

The farmer would hand over the crop in lieu of his taxes, the rural moneylender (mahajan) would take the grain and give cash to the local revenue officer. The mahajan, often times acted as an agent to the city-based banker. In the absence of the rural lender the encashment of the land revenue was delayed.

If the mahajan was unavailable, the revenue officials took the initiative to invite the banias (merchant cum moneylender) to buy the produce. The banias would purchase the state share of land tax.

However, the merchant/mahajan/bania was not free to determine the grain rates on their own. The office of the prime minister (diwan) set the crop rates for all the districts (pargana) in the state, by looking at the demand and supply in the internal and external market.

The grain was sold by the district official to the merchant at the fixed rate. The sale of the state share was made in the presence of the chaudhari who testified to the sale and the rate at which the crop was sold.

The practice of centrally fixing the crop rates and the presence of a chaudari at the time of sale was to reduce theft on the part of the official and merchant.

The role of the bania was not limited to purchase of grain, he was vital in commuting the transaction into cash.

The revenue thus collected by the district official had to be transferred to the state treasury. The district official deposited the tax revenue with the local moneylender who after receiving the money issued a hundi in favour of the office of the diwan.

The office of the diwan encashed the hundi by handing it over to the capital-based banker (Sarraf or Shah) after paying some commission. Commission varied on the location of where funds were being sent ranging from 1.5% closer to Amber to 2.5% in the districts.

In the districts of Amber there were plenty of trustworthy moneylenders who had the ability and connections to transfer funds to the state treasury through hundis.

The royal court (darbar) also needed the services of the native bankers/lenders to transfer funds from the state treasury to the districts and far off rural villages, in case of earthquakes or loss of crop due to pests or disease outbreak. During famines, interest rates could rise to as high as 25% per year, hence to ensure liquidity and provide food for the people, rulers depended on rural lenders.

In times of war, the district officials collected the taxes in advance to fulfill state demand. The rural moneylenders often gave advances to the district officials to fulfill their tax quotas.

The peasants often had no money before the harvest to pay the tax demand and were forced to borrow from the rural lenders.

All of this was made easier because of the hundi system.

Selling the Right to collect taxes in times of stress

Under Mughal rule, it was common practice to auction tax collection to the highest bidder.

This system was called Ijara, and the collector was known as the Ijaradar. The collector would pay a fixed amount upfront to the ruler. Buying Ijara was a profitable investment, and under this system, both the state and moneylenders were united in exploiting the peasantry.

The credit extended by the collectors - to rajas and the common folk - kept the economy running and ensured the treasury had funds to pay its debts.

This form of revenue farming was prevalent across the Mughal Empire, including in the Rajputana region.

But by the late eighteenth century Mughal dominance was fading leading to political instability. The Rajputana nobles revolted, and to keep power for themselves, they sought the help of the Marathas.

The Marathas demanded protection money from individual chieftains to safeguard them from other Rajput chieftains. Huge loans had to be raised to pay tributes to the Marathas, the East India Company, and the military leader Amir Khan, putting a strain on Rajput state finances.

As the demand for cash rose, the Rulers sold rights to collect various taxes, including land taxes, mining rights, tolls for passengers to cross their territories (rahdari), and police fees (kotwali), to the highest bidders.

The indebted ruler would hand over the right to collect taxes to his financier.

Not to be left behind, urban traders and bankers started speculating in revenue farming.

The political uncertainty strengthened powerful feudal landowners (jagirdars) who exacted further taxes on goods passing through their lands.

In Marwar about twenty taxes were levied under different names on the sale, import and export of goods. Many of them were enacted by the state while others were charged by the landowners (ijaradars or jagirdars) treating the area as their own fiefdoms.

Expanding operations beyond Rajasthan

In almost all villages in Jodhpur and Amber the money lenders occupied positions as revenue collectors, assessors (amil and amin) and treasurers (potedar), at the district and state levels. These offices were treated as a source of profit and were sold to the highest bidder. Through hundis, the buyers could provide the state with advance and guaranteed revenue, a practice common in both urban and rural areas.

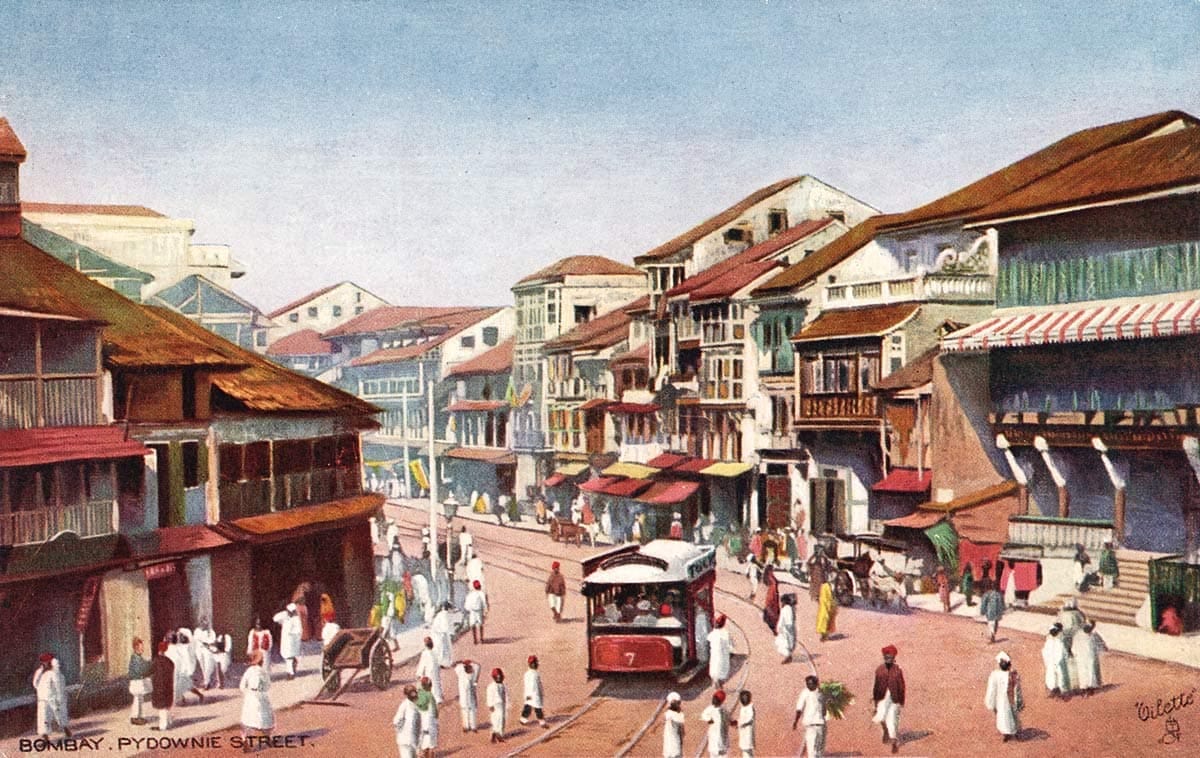

The merchants and bankers continued expanding their trading operations beyond Rajasthan though they kept their business headquarters in it. When the British established new and safer trade routes, they relocated to cities like Bombay, Patna, and Calcutta, viewing this as an opportunity to escape the heavy burden of taxes. Following new opportunities they spread across the subcontinent.

The native entrepreneurs of the 18th and early 19th century generally did not deal with other people’s money; they were largely lending their own money. Thus, indigenous banking was primarily money lending. They also engaged in money changing, issuing and discounting of hundis, insurance and trade.

But, the moneyed class remained aloof from industrial undertakings. Because the colonial economic structure offered little returns for investing in industries.

The merchant class dominance in society continues in modern day India.

Jagat Seth

In 1757, an Indian wealthy banker played a pivotal role in securing victory for the East India Company in the Battle of Plassey: marking the start of British rule over the subcontinent. The banker was from the house of the ‘Jagat Seth’.

Hira Nand Sahu was the founder of the house ‘Jagat Seth’. He came to Bihar in the 17th century as a banker and an army purveyor of Raja Mansingh of Amber.

His successors would expand their banking operations throughout the east of India.

A few decades later, a cash strapped Mughal Emperor turned to Manik Chand, a money lender who provided him with the much-needed funds. Pleased with him, the emperor bestowed the title ‘Nagar Sheth’ upon him.

Nagar Sheth's successor expanded the family business and worked closely with subsequent rulers. In recognition of the family's contributions to the Mughal administration, the title 'Jagat Seth' was bestowed upon them. This title, meaning "banker to the world," would be passed down to successive males of the family.

The foundation of their wealth was their access to the Mughal court. Tax collection, minting of coins, and moneylending to the rulers formed the basis of their operations. The biggest trading houses of the time, including the English, Dutch, and French Companies, sought to keep Jagat Seth in good humor and worked to gain his favor. All the money in Bengal, the richest province in India, passed through the Seth's hands. Three out of four rupees collected as revenue went straight to Jagat Seth, against loans advanced to the Nawab of Bengal.

Robert Orme, the official historian of the Company, described Jagat Seth as the greatest banker and money changer in the world at the time.

The family built their business in Murshidabad, West Bengal, under the reign of the Nawab of Bengal, who was under the suzerainty of the Mughal Emperor in Delhi. By the start of the 18th century, the family had become the largest banking house in the country.

Jagat Seth had the heft to make or break rulers.

Ascending to the throne in 1756, Nawab of Bengal Siraj-ud-Daula, was known for his temper tantrums, unprovoked acts of violence, and sexual misconduct. His name instilled fear in the hearts of people. During his short reign, he made many enemies, including Jagat Seth, the East India Company, and Mir Jafar, the Nawab's chief of army.

On one occasion, the Nawab demanded Rs.30 million to equip his army and wage war. Jagat Seth refused. In a fit of rage, the Nawab struck Jagat Seth in the face and threatened him with circumcision. Insulted Jagat Seth plotted with Mir Jafar to overthrow him.

With Jagat Seth providing the brains and financial muscle, it was decided to harness the Company's military forces, led by Robert Clive, to overthrow the Nawab.

Due to their plotting, in the ensuing war, the Nawab's army was defeated. As victors, the Company received approximately £200 million, and Robert Clive received £22 million in modern terms from Jagat Seth and the treasury of Bengal. The Battle of Plassey victory marked the beginning of British rule in India.

Mir Jafar took over as the new Nawab and was succeeded by Mir Qasim. Frustrated by being under the control of the Company, Mir Qasim fought against the Company and lost. After his defeat, incensed at the treacherous role played by Jagat Seth during the Battle of Plassey, Mir Qasim murdered Jagat Seth and his cousin in 1763.

The family fortune of the successor Jagat Seths dwindled over the next century, in line with their Mughal patrons. The last member of the family died in 1912, their fortunes a tale of the past, surviving on a pension given by the British.

References

The Ijara system- The Role of Indigenous Banking During Eighteenth Century, Rajputana by Meera Malhan

Information on Hundi’s and Marwaris- Indigenous Banking and the State in the Eastern Rajasthan during the Seventeenth Century by G.D. Sharma

The Marwaris: Economic Foundations of an Indian Capitalist Class by G.D. Sharma, this is a chapter in Business Communities of India edited by Tripathi

Jagat Seth story- The Anarchy by William Dalrymple and The Rise and Fall of the Jagat Sheths by Joseph Rozario

Thank you for making it till here! All the articles on Filtered Kapi take a lot of time, love and care to write. Tell me what you liked, enjoyed, disagree with by leaving a comment so that I know you exist, and I don’t feel like I am a weirdo talking into the void!

P.S. If you enjoyed this article, you might also like my previous piece, which led me to many of the cool details featured in this story. How the Rajas of India lost control of their right to coin money

Filtered Kapi #71

Intersection of History and Finance - a very fascinating and gripping read.! Thank you.!

Enjoyed this. Thank you.